Construction procurement guide: procurement method selection

Introduction

Under the NSW Government Procurement Policy Framework, the procurement process is divided into 10 steps.

The initial steps involve identifying a service need and considering the options available to meet that need.

If the preferred option is the construction of a capital works project, then step 5 (procurement strategy) requires the agency to determine and document how the project will be delivered.

This involves deciding how the project will be managed, what contracts will be involved and how risk will be allocated in those contracts.

This guide has been prepared to assist NSW Government agencies to select appropriate procurement methods for construction projects. It is intended to be used for construction projects valued at more than $1 million, or with a high associated level of risk, that are being undertaken for agencies that are not accredited to manage construction projects under the Accreditation Program for Construction Procurement.

A procurement method includes:

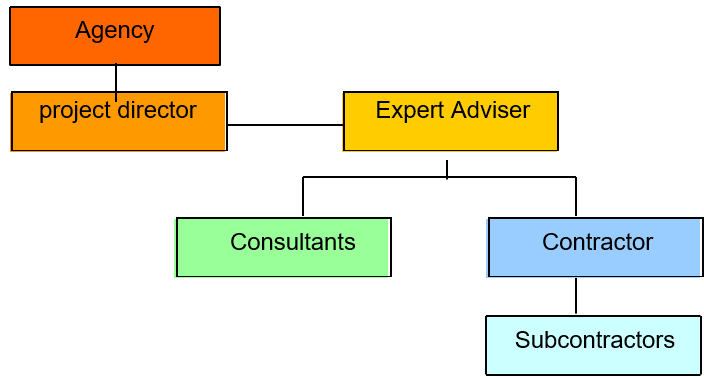

- a management structure that may involve in-house personnel, an expert advisor from an accredited agency or the private sector (whose role is to manage the project) and other service providers

- contracting arrangements for design, construction, maintenance or operation activities, and

- subcontract arrangements.

Selecting an appropriate procurement method will assist in obtaining best value for money and managing procurement risk. It will make effective use of both government and private sector resources and balance critical factors such as:

- value for money

- cash flow rate

- timeliness

- quality of design, and

- quality of construction.

The procurement method will also reflect the desired allocation of risks between the construction contractor(s) and other service providers, and the agency for which the work is being constructed (represented by the principal in the contracts).

This guide describes the elements of a procurement method, including different types of contracts commonly used for construction projects and special subcontracting options. They discuss factors that influence the selection of an appropriate procurement method, including the management and allocation of risks.

The Principal in a construction contract guide provides guidance to assist agencies in determining who should be named as the principal in the contracts.

Management structure

Procurement policy

Treasury Circular TC 04/07 introduced an agency accreditation scheme that prescribes requirements for agencies undertaking capital works projects. Certain agencies are accredited under the scheme.

Accreditation applies separately to the planning phase and the delivery phase of a project. An agency may use its own staff to manage phases of the project for which it is accredited.

The agency may obtain partial accreditation for a particular phase of a specific project if it can demonstrate to NSW Treasury that its in-house personnel have the expertise necessary to manage the procurement process for that phase.

An unaccredited agency that intends to undertake a capital works project must, at the outset, determine its value and its level of risk, using the project profile assessment tool available on the NSW Treasury website.

For capital works projects valued at $1 million or more, or with a high level of associated risk, the NSW Government Procurement Policy Framework requires government agencies that are not accredited to:

- comply with the NSW Government procurement system for construction, maintained by the Department of Finance, Innovation and Services, and

- appoint an external adviser (from an accredited agency or a prequalified private sector service provider) to manage the procurement process.

The NSW Government procurement system for construction includes:

- this guide for selection of a procurement method

- a suite of standard form contract documents

- service provider selection guide and procedures

- contract management guidance material

- performance management systems

- contract dispute resolution guide.

For more information, contact the NSW Procurement Service Centre on nswbuy@treasury.nsw.gov.au

Even when an agency is not managing a project using its own resources, it needs to make financial and risk management decisions and to manage the engagement of the external expert adviser. The agency must nominate an officer to take responsibility for managing the agency’s contribution to the project. That officer may be called the project director or project sponsor.

The management structure may be represented as shown in Figure 1. Lines of communication in a typical management structure.

The role of the expert adviser

The role of the expert adviser is to efficiently manage the range of activities involved in delivering the project and in particular the interface between the agency and the private sector.

This involves planning and coordinating the activities of consultants, contractors and other service providers. It usually includes preparing (or managing the preparation of) appropriate tender documentation, managing tender processes and administering contracts.

Before engaging an expert adviser to assist in the procurement process, an agency must determine what specific services the expert adviser is to provide.

Those services will depend on the proposed management structure for the project and the degree of control the agency wishes to retain. These in turn will depend on the expertise of the agency staff available to manage the construction work and related services.

The expert adviser’s management services can be described in terms of the project phases the expert adviser will be required to manage and other aspects of the proposed engagement including:

- the extent of the expert adviser’s responsibilities and authority

- the conditions of the engagement

- communication and reporting procedures

- performance measures and deliverables, and

- how payments will be determined.

One key issue for the agency to determine is what contractual authorities the agency will retain and what authorities will be delegated to the expert adviser.

The agency cannot delegate authority to commit or incur the expenditure of public moneys to a person that is not a public sector employee. If the expert adviser is a private sector firm, the agency must decide what officers within the agency are to exercise relevant financial authorities and arrange appropriate delegations.

The agency must also establish effective communication procedures between those officers and the expert adviser, to ensure that contractual actions and decisions that could incur expenditure are taken promptly and do not incur costs as a result of delays.

Engaging an external expert adviser

An agency may directly engage an accredited government agency to act as its expert adviser or project manager. If an accredited agency is engaged, then tenders for the expert adviser services need not be called and the services can be provided under a memorandum of understanding or service level agreement between the agencies.

If the agency wishes to engage a private sector company as its expert adviser, then tenders must be called.

The Department of Finance, Innovation and Services maintains lists of organisations prequalified to perform the roles of project director or project manager. Unaccredited agencies are required to engage expert advisers from those lists.

The engagement must specify the role of the expert adviser and must be under appropriate terms and conditions. For agencies that are not accredited, there is a standard form of tender document for project management services. The standard form provides a basis for engaging a project director or project manager. It is designed to be adapted to suit the particular needs of the project and the agency.

It may be appropriate to engage the external adviser under a lump sum contract if the role and responsibilities can be clearly specified when the engagement is established. Special provisions should be included in the contract so that the parties (the agency and the external adviser) understand and agree upon the method of calculating the amount of each progress payment.

An alternative to a lump sum contract is a contract with a schedule of rates or lump sums. Under this arrangement, progress payments can be calculated on the basis of the achievement of specific outcomes, such as the approval of submissions, the preparation of documents or reports or the completion of contract administration functions.

Other service providers

Before making decisions on engaging consultants and construction contractors to provide services and carry out work, it is important to understand the concept of risk allocation. This guide discusses issues related to risk allocation through contracts.

There are standard forms for construction for the preparation of tender documents for:

- consultancy agreements

- GC21 construction contracts, for work valued at $1 million or more or complex in character

- Minor Works construction contracts, for work valued at less than $1 million and straightforward in character

- Mini Minor Works construction contracts, for work valued at up to $50,000.

The standard forms assist agencies to carry out capital works procurement efficiently and effectively and to manage procurement risk. They:

- are developed and maintained to incorporate current procurement policies

- include reasonable and consistent risk allocation provisions

- provide guidance to assist users to select options appropriate for their circumstances.

For capital works projects worth more than $1 million, agencies that are not accredited are required to use these standard forms to engage private sector service providers and contractors.

Expert advisers engaged by agencies that are not accredited are expected to use the standard forms. Agencies are encouraged to use the documents for projects of lesser value to assist in managing procurement risk.

Selecting service providers

The Department of Finance, Innovation and Services maintains a service provider management system which includes prequalification schemes for project managers, project directors, consultants and contractors.

The prequalification schemes apply to construction and construction-related work of various kinds and different values. The service providers are prequalified on the basis of their capabilities and their performance is monitored to ensure standards are maintained. There are incentives to improve performance by offering increased tendering opportunities to better performers.

Unaccredited agencies undertaking construction projects valued at more than $1 million or of high risk are required to use the Department of Finance, Innovation and Services system to select tenderers for the associated consultancy agreements and construction contracts.

Managing service providers

If the agency engages an expert adviser that is a private sector firm, the consultants undertaking the design and other services are generally engaged by the agency, under contracts with an entity representing the agency (the principal).

The principal may be a minister or, where the agency is a legal entity, the board. For more detailed guidance, refer to the Principal in a construction contract guide.

The expert adviser will provide a person to act as the representative of the principal, carrying out contract administration functions to the extent defined by the agency in the project management services agreement.

Note that, if the external adviser is a private sector firm, then decisions involving the commitment or expenditure of public moneys must be made or ratified by agency personnel with the appropriate delegated authorities.

As an alternative, design consultants may be engaged as sub-consultants to the expert adviser. This is common where the expert adviser is a government agency. If the expert adviser engages the sub-consultants, then the agency does not directly instruct the sub-consultants and holds the expert adviser responsible for their work.

For large scale projects, a cost planner is often engaged to prepare estimates and monitor cash flow and variations in actual cost over estimate. An agency may choose to engage the cost planner itself, independently of the expert adviser. This is common where a non-traditional arrangement such as a managing contractor contract is adopted.

A construction contractor is generally engaged by the agency (under contract to a minister or the agency’s board) and managed by the expert adviser.

If the construction component of the project requires multiple contracts, and particularly if these are trade-based contracts, the agency or its expert adviser may appoint or engage a construction manager.

The construction manager oversees the various construction-related aspects of the project including programming, managing work flow, coordinating different contractors and controlling costs. The role of a construction manager is discussed in more detail in the Single and multiple contract options guide.

Procurement advice

In some circumstances, at the request of the agency, the expert adviser may be supported by a procurement adviser from the Department of Finance, Innovation and Services, who will ensure that the procurement processes comply with the NSW Government procurement system for construction.

In all circumstances, ad hoc advice is available from the NSW Procurement Service Centre at nswbuy@treasury.nsw.gov.au

Project characteristics and risks

The selection of a procurement method must take into account characteristics and constraints that are specific to the project. An appropriate procurement method will be effective in mitigating the risks inherent in the project.

Project characteristics that can affect the choice of procurement method include:

- funding source and availability

- flexibility of budget including contingencies

- cash flow requirements and restrictions

- required start date

- time available for completion

- flexibility available in the program

- staging requirements

- government policies impacting on the project

- requirements of regulatory authorities

- interfaces with other contracts and projects

- stakeholder attitudes and influence

- coordination with other agencies

- principal supplied materials, for example furniture

- environmental, heritage, archaeological issues

- extent of control over design activities

- resource limitations: availability and expertise

- completeness and clarity of the brief

- likelihood of changes from outside the agency’s control (political, funding or technological)

- status of investigation work

- availability of design or performance standards

- new work, refurbishment, maintenance or demolition

- building or civil engineering or other

- removal of hazardous materials or site rehabilitation

- specialist technical requirements or technology

- geographical location

- greenfield or developed site

- premises are currently occupied or vacant

- availability of site services

- unknown conditions requiring investigation or preparatory work

- value of project

- desirability/availability of innovative designs, construction techniques, proprietary systems

A common project constraint is the time available for project completion. The Estimating contract times guide provides guidance on the selection of realistic and appropriate time frames for typical building contracts of different values and complexities.

Factors that can expose the project to risk and need to be considered in selecting a procurement method are illustrated in Figure 1 - Factors that can influence the selection of a procurement method.

As an initial step in determining an appropriate procurement method, document the project characteristics and constraints. Form A - General project data provides assistance for this process.

Risk identification and allocation

The primary objectives of a construction project are generally to meet asset outcome, time, cost and quality requirements such as:

- satisfying the needs of the community or asset users

- completing the project on time or to a required schedule

- meeting construction or subsequent operation budget constraints

- complying with predetermined cash flow rates

- providing required standards and finishes

- safeguarding the environment

- incorporating new technology.

Project risks

Construction projects are typically complex and there are many factors that can jeopardise the achievement of project objectives. Managing project risks requires continuing effort throughout the duration of a project.

A project can be placed at risk because, for example:

- funds are inadequate for the project scope required to meet service needs

- the required work is not clearly defined

- the requirements of regulatory authorities are unknown

- changes to design parameters occur because of changing government policies or stakeholder requirements

- stakeholders do not support the project

- agency resources are insufficient or inexperienced

- agency-initiated changes to the design are not controlled

- unexpected site conditions (latent conditions) are encountered, for example hazardous materials or subsurface obstacles

- existing site services are inadequate

- the present occupiers of the site are uncooperative

- coordination with other agencies and other contractors causes difficulties

- the principal does not supply required materials or information on time

- rapid changes in the technology involved affect the suitability of the design.

The selection of a procurement method is a critical decision that can mitigate or exacerbate project risks. However, it must be understood that an agency cannot divest itself completely of project risks. Different procurement methods not only impact differently on project risks, but each has its own inherent risks.

If design consultants are engaged by the agency to prepare documentation for a construction contractor, then the agency bears a risk of claims from the construction contractor because errors and omissions in that documentation.

Conversely, if the contractor is responsible for the design, the agency bears a risk that the contractor’s design will not fully meet the agency’s expectations.

Deciding what proportion of the design to include in a construction contract involves trading off these different risks.

Risk allocation through contracts

Risk allocation means determining where the liability and responsibility for the various risks involved in the project will lie.

Liability under a contract is generally shared between the principal and the contractor, with some being covered by insurance or reallocated to other parties.

The principal to the contract generally drafts the contract document and determines how risks are to be allocated.

Contracts are tools for allocating responsibilities and risks.

The most appropriate form of contract for a construction project will depend on:

- the risks inherent in the project

- the relative risk management capacities of the agency and potential contractors

- other objectives of the agency.

In deciding on the allocation of contract risks, the agency can choose to either:

- accept the risk and pay any extra costs that result if the risk is realised, or

- pass the risk on to a contractor (and possibly pay an associated premium to the contractor).

Passing project risks on to a contractor through a contract does not relieve the agency of the related costs.

If the agency retains a risk, then it will pay the resultant costs if the risk event occurs. If the agency allocates the risk to the contractor, this can be expected to increase the price the agency pays for the work, because the contractor’s price will include an allowance for unforeseen circumstances or unmeasurable risks.

Logically, passing more risks on to a contractor will increase the contract price. Further, the agency will pay the extra cost of a risk even if it does not eventuate. It is usually more cost-effective for the agency to accept a certain proportion of the risks than to pay the correspondingly higher contract price.

There are some risks that cannot be transferred to a contractor. These include changes made to the design after the contract is awarded or breach of contract by the principal.

There may be other risks inherent in a project that are considered too expensive to transfer to a contractor. On such risk could be the risk involved in obtaining approvals from other authorities, which could cause long time delays and associated costs.

Contract provisions identify and allocate risks to avoid disputes over which party is liable to pay the costs when a risk eventuates. In allocating risk between the principal and a contractor, the following questions should be considered:

- Who has the greater degree of control over the eventuality?

- Who is best placed to assess and manage the risk?

- Who can best share/cover the risk with another party such as an insurer?

Allocating to a contractor a risk that cannot be realistically priced may lead to the contractor inadequately or inappropriately allowing for the risk, particularly where competitive tendering is involved. This is not in the interests of the agency.

If the risk eventuates and the contractor’s costs exceed the allowance in the tender, the contractor may seek compensation under the contract or otherwise by way of legal action. Such claims are likely to cause disputes and significantly increase the cost of the project.

If the contractor has not adequately allowed for the risk, another potentially more costly and disruptive possibility is that the contractor encounters financial difficulties and is unable to complete the work.

If a contractor goes into liquidation, the agency may be unable to recover the associated costs even if the contract provides for the principal to complete the work at the contractor’s cost.

An agency must be careful in deciding what risks it will allocate and must seek to allocate those risks to external entities (consultants and contractors) with the financial, technical, management capability and capacity to perform the work.

The Contract options guide describes in more detail the benefits and risks associated with various types of construction contracts.

Form B (Preliminary assessment), Form C (Traditional contracts – Assessment of whether multiple contracts are required) and Form D (Traditional contracts – Selection of a contract type) provide a framework for determining a suitable procurement method on the basis of the risks specific to a particular construction project.

Contracting options

Government construction works are generally carried out through contracts with private sector service providers and contractors. Determining a procurement method essentially involves deciding what parts of the work an agency will contract out and how that work will be packaged.

The agency may wish to select and manage design consultants under separate agreements or it may engage a construction contractor to undertake some of the design work.

The main contractor can be made responsible for managing the whole of the project or a separate contract may be awarded for management of the construction activities.

There may be benefits in the agency engaging a number of different construction contractors under separate contracts.

Contracting options are generally differentiated by describing the responsibilities given to the construction contractor.

Traditional contracting options commonly used for government construction work in NSW include:

- Developed design (or Construct only) (DD). Where the contractor constructs work in accordance with a fully developed and documented design provided by the agency.

- Design development and construct (DD&C). Where the contractor develops the design from a concept or preliminary design provided by the agency and constructs the work.

- Design, novate and construct (DN&C). Where the contractor takes over from the agency a previous contract for the design work, completes the design and constructs the work.

- Design and construct (D&C). Where the contractor prepares a design on the basis of a performance or functional brief and constructs the work.

- Guaranteed maximum price (GMP). Where the contractor tenders a fixed price and the contract limits the contractor’s entitlements to claims for extra.

A contract can include responsibilities for maintenance or operation. This can be of particular benefit with a D&C or DD&C contract, where the contractor’s involvement in the design allows scope for improvements that will reduce operation or maintenance effort and costs.

A single contract has the advantage that the contractor takes the construction coordination risks. But under some circumstances, there may be benefits in using multiple contracts, where the agency awards a number of contracts for the work, either for different trades or discrete parts of the work, perhaps using a construction management approach, where another agency or contractor is engaged to manage those contracts.

If early contract packages are awarded for items with long lead times, the agency’s coordination risks can be reduced by novating the early contracts to the main construction contractor.

For projects with special needs, the following non-traditional arrangements can offer advantages:

- Managing contractor. Where the contractor is engaged early in the life of the project to manage the scope definition, design, documentation and construction of the project works using consultants and subcontractors, under a contract providing for payment of fees and involving incentives for maintaining actual costs within targets.

- Alliance contract. Where the agency enters an agreement with other entities to undertake the work cooperatively, reaching decisions jointly by consensus, using an integrated management team and intensive relationship facilitation, sharing rewards and risks and using an open-book approach to determine costs and payments.

- Privately financed project (PFP). Where a private sector entity finances, designs and constructs the asset, possibly owns the asset for a period, and achieves a financial return on its investment, for example by charging for use of the asset over a concession period.

The circumstances under which the above options would be appropriate, and their benefits and risks, are described in more detail in the Contract systems guide.

Figure 2. Control / responsibility chart shows how control over the phases of a project is allocated to either the agency or the contractor, depending on the type of contract used. Note that allocating control for project activities also allocates responsibilities and the associated functional, financial and program risks.

Determining an appropriate contracting option

The appropriate procurement method for a project will depend on the characteristics of the project, the factors that impact its delivery and the desired risk allocation. An appropriate selection will:

- obtain value for money

- manage risk

- meet project objectives.

The impacts of some of the significant factors that impact the selection of a suitable procurement method are described below.

Source of funding

A privately financed project (PFP) may be an option if:

- government funding is limited

- it is critically important that the asset be constructed within a given timeframe in order to provide services, and

- the project has the capacity to offer the private sector significant returns on the capital investment.

A PFP may be a viable option if:

- the public can be charged to use the asset (for example, a road)

- the asset can be leased back to the government (for example, a building), or

- the government can provide some other benefit in return for the asset (for example, a parcel of land or rights to air space above a building).

If there is no opportunity for the private sector to achieve a return on the investment, then a PFP will not be viable. If it is not possible to clearly describe the required outcomes, including the required services in terms of performance, then a PFP will not be suitable.

PFPs are generally applied to large scale, high-value projects (worth more than $50 million) due to the complexity of the contractual arrangements and the associated high costs of tendering, negotiating and establishing agreements.

Detailed guidance on assessing whether a PFP is a suitable option is given in the NSW Treasury publication Working with Government: Guidelines for Privately Financed Projects, available on the NSW Treasury website.

Complexity and risk profile of the project

An extremely complex, high-profile project whose scope and risks are uncertain and which involves many stakeholders with disparate views may warrant the special management arrangements available through an alliance. The project would generally also have a challenging timeframe and a value of more than $50 million.

The cost of developing and maintaining the special relationships required for an alliance must be considered, and the fact that the liability of project partners other than the funding agency is normally capped. The actual project costs are met by the funding body under an open book accounting arrangement, so the financial risk is not transferred to the contractor.

This type of arrangement is suitable if it is unlikely that the difficulties involved in the project could be surmounted without all the parties working together as a team, sharing the costs and the risks.

Design brief

An undefined brief can be developed successfully through an alliance or managing contractor contract, achieving the added benefit of input from the contractor during the design phase.

This includes situations where the requirements are unknown due to undetermined requirements from other agencies or stakeholders or incomplete site investigation.

Other benefits can be gained through harnessing the expertise of a construction contractor, for example to produce an improved design.

The advantages of these non-traditional arrangements will not be fully realised unless the agency is prepared to accept the contractor’s advice. It may be appropriate to use multiple contracts under such circumstances, if it is necessary to commence the construction work early in order to achieve expenditure or other objectives and the agency wishes to retain control of the design.

With a PFP or a traditional type of contract, the project brief (including performance requirements if there is a service component such as maintenance or operation) must be described clearly in the tender documents or there is a high risk either that the desired outcomes will not be achieved or that additional costs will be incurred because variations need be directed in order to achieve them.

Variations directed after a contract is let are likely to cost more than the value of the extra work because of possible delay and disruption costs.

It is not desirable to enter a PFP or traditional contract if stakeholder requirements are unknown because delays could occur, possibly resulting in additional costs. Even if the contractor is charged with obtaining approvals, stakeholder delays could prove costly. Furthermore, some stakeholder requirements may not be fully satisfied in the final product, diluting the success of the project.

The primary difference between the different types of contracts traditionally used for construction work is the amount of design responsibility allocated to the contractor.

If it is possible to define the project requirements in terms of functional or performance criteria and the agency is prepared to relinquish control of the design to the contractor, then a design and construct contract may be appropriate.

This type of contract encourages the use of proprietary items or systems. The asset may be constructed to common industry standards, or the agency could provide a brief that includes standards for specific components and finishes.

A design and construct contract reduces the agency’s exposure to costs incurred due to errors and omissions in the design documentation. It also usually allocates the risk of unanticipated site conditions to the contractor, which is likely to be reflected in higher tender prices.

A design and construct contract does not necessarily provide the lowest cost asset but can provide value for money if the contractor has the opportunity to adopt a proprietary system or develop an innovative design or use innovative construction techniques. It is particularly suited to a situation where there are a number of different viable design solutions available to meet the agency’s needs.

If industry cannot offer innovation or the agency is not flexible in its requirements, these advantages will not eventuate. A design and construct contract, like a PFP, involves a relatively high risk that the finished product will not fully meet the agency’s expectations. The more detailed the agency’s brief, the lower the risk of dissatisfaction with the end product.

If the agency has a set of facilities standards that clearly define the required components and finishes, then a design development and construct contract may be applicable. The agency will have more control of the design than with a design and construct contract, as it determines the concept design or site layout, and is more likely not to be disappointed with the constructed asset.

However, the agency accepts the risk of errors and omissions in the design work it provides to the contractor. Novating the design contract to the construction contractor (see Novation, in the Contract options guide) can reduce these risks.

Under a design development and construct contracting arrangement, tenderers are asked to price the work in the absence of a fully developed design and can therefore be expected to allow for the associated risks in their prices.

Introducing the additional complication of novating one contract to another can also lead to increased prices from both contractors. The design contractor may be reluctant to commit to a novation to an unknown party.

The construction contractor may be unwilling to contract with the particular design contractor or it may be reluctant to accept the risks of design work carried out under the supervision of the agency.

The more design the agency manages itself, the greater the likelihood that it will be satisfied with the final product and the more risk it accepts for possible design errors.

A developed design contract is the most likely to produce an asset that meets the agency’s requirements, but it exposes the agency to the risk of claims due to errors and omissions in the tender documentation on which the contractor based its tender price.

Time constraints

Incorporating design responsibilities into a design development and construct or design and construct contract can assist in achieving time targets, providing the contractor has a contractual obligation to complete the work on time that includes incentives or penalties.

The contractor has flexibility to commence construction before the detailed design is completed in order to meet program commitments. This flexibility is not available if a single developed design contract is adopted.

A managing contractor contract can assist in meeting time constraints, including achieving an early start to construction, since the contractor has the capacity to overlap design, design development or construction activities. It avoids the delays that occur with a design and construct contract, where there is a need to clearly define requirements and to call and evaluate complex tenders.

A multiple contracts arrangement can be used to manage time constraints or achieve staging.

Budget limitations

For complex projects where it is essential not to exceed an agreed budget, a managing contractor contract may be appropriate.

Once the contractor guarantees a construction sum, the asset will be constructed for no more than that amount, providing the agency does not direct variations.

The arrangement relies on the contractor managing the budget and identifying and advising if agency requests will increase the project cost.

The maximum benefit is achieved when the contractor is involved in the design or design development, but its success depends on whether the agency is willing to tailor its requirements to the budget.

Budget increases can occur if:

- the contractor fails to advise of the effects of requested changes, or

- the agency insists on making those changes without adopting corresponding measures to generate savings.

The contract will provide for the original target construction sum to be increased because variations that are directed and the contract price is not guaranteed until the contractor is confident that the design is determined.

Because it involves a cost-plus arrangement for work carried out by consultants and subcontractors, and there is no competition involved in quoting a guaranteed construction sum, a managing contractor contract is unlikely to offer the lowest price. Its advantage is to reduce the risk that the predicted end cost will be exceeded.

A managing contractor arrangement is generally only used for projects worth more than $20 million because it includes a relatively high contractor management fee.

A guaranteed maximum price contract may be a suitable option if certainty of end cost is critical, but tender prices are likely to be high to compensate for the risks and because the number of contractors willing to enter into such a contract is limited.

Awarding multiple contracts may also be appropriate if the budget is limited. This offers flexibility but not certainty in relation to the final cost.

It may assist if there is no objection to reducing the scope of the project as contract packages are awarded or reducing quality standards, in order to meet the budget.

Multiple contracts may be appropriate if the full amount of funding required is not secured at the time construction must commence in order to meet political or other commitments and the project scope is flexible.

Cash flow restrictions

A managing contractor contract may be suitable where achieving a predetermined cash flow is essential, if the cash flow limitations are specified in the contract.

Multiple contracts can also be appropriate, as they give the agency more direct control of expenditure.

Physical constraints

If the site is restricted and the work packages are interdependent, then a single contract should be the first preference.

If a multiple contract arrangement is necessary due to pressing budgetary or timing constraints or because of unknown site conditions (for example, the presence of archaeological relics), then the option selected must be construction management, where a specialist company or expert construction agency is engaged to coordinate and manage the contracts.

Pricing of contract risk

A developed design contract can be expected to attract tender prices close to the actual cost of the work, since the tenderers have the clearest idea of what is required and do not have to allow for risks such as documentation errors or conditions that may be discovered during investigation and design development.

More companies are likely to be interested in tendering, which will increase competition and drive prices down.

The agency bears the risk of errors in the documented design and, usually, of unforeseen circumstances and conditions, which can lead to increases in contract costs.

However, the additional costs will only be incurred if a risk event occurs. Engaging competent designers and carrying out adequate investigation will minimise these risks.

Where the contract includes a greater design component, tender prices are likely to be higher to allow for the greater transfer of risk to the contractor, and competition will be more limited.

Maintenance requirements

If the asset will require significant maintenance effort that is directly impacted by the design and construction work and there is no clear benefit in the agency arranging maintenance itself (for example, if there is an existing separate maintenance contract for a portfolio of assets), then the contract could include maintenance of the asset for a prescribed period, say 10 years.

This option is most effective when the contractor is responsible for a significant part of the design and has the capacity to tailor it to suit the proposed maintenance regime.

There may be a cost penalty because the construction contractor is unlikely to have a maintenance arm and the price paid by the agency will include the cost of the contractor arranging and managing another entity to undertake the maintenance activities.

However, the agency should benefit from increased consideration of maintenance issues during the design or construction phases.

Figure 3. Procurement options summary illustrates the procurement method options commonly used.

Form B (Preliminary assessment), Form C (Traditional contracts – Assessment of whether multiple contracts are required) and Form D (Traditional contracts – Selection of a contract type) provide a framework for considering the above criteria for a specific project. They can assist in identifying an appropriate contracting arrangement.

The output generated through use of the forms should be tested against the detailed descriptions of options and their features provided in the Single and multiple contract options guide to confirm that it is a reasonable and justifiable choice.

Subcontract options

Construction contractors engage subcontractors to carry out packages of work of different types, often based on particular trades. As far as the principal is concerned, the contractor is responsible for the performance of the subcontractors and bears the risk of their failure to perform.

Where the agency wishes to exercise some control over the subcontractors used for specific parts of the work, the agency can require the contractor to engage a preferred subcontractor (known as a selected subcontractor in AS 2124 contracts).

The contractor is responsible to the principal for the quality and timeliness of the preferred subcontractor’s work, as for any other subcontractor.

Under a preferred subcontractor arrangement, a list of subcontractors that are acceptable to the agency is included in the main construction contract. The contractor selects and enters a subcontract with one of these.

This option can be applied to suppliers of special equipment or specialist trade subcontractors, such as security or ICT suppliers, that are sought because of their specialist knowledge or expertise.

In order to identify suitable preferred subcontractors to include in the contract, the agency may call for expressions of interest from firms with particular capabilities or the ability to supply particular proprietary equipment.

Another option, discussed in more detail in the Novation section in the Single and multiple contract options guide, is for the agency to engage a specialist contractor for the supply of long lead time equipment or to commence certain early work before the main construction contract is awarded.

The early contract can be novated to the construction contractor. The construction contractor then takes on the risk and responsibility for the novated contract as if it were a subcontract arranged by the construction contractor.

Related resources

Find more resources on the construction category page.