Construction procurement guide: contract systems

Introduction

This guide briefly describes the following types of contracts that are commonly used to deliver construction projects:

- documented design (also known as construct only)

- design development and construct (DD&C)

- design, novate and construct (DN&C)

- design and construct (D&C)

- design, construct and maintain (DCM)

- guaranteed maximum price (GMP)

- managing contractor

- alliance

- privately financed project (PFP).

For each type of contract, guidance is provided on:

- when its use would be appropriate

- its benefits, and

- associated risks.

Table 1 below indicates in general terms which phases of a construction project can be incorporated into each type of contract.

Note that the procurement process is in effect a continuum, and that, provided the required scope of work is clearly defined, a contract can be drafted to incorporate whatever proportion of the design, documentation, construction or maintenance is desired.

| Contract type | Concept design | Design development | Documentation | Construction | Maintenance / Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Developed design | Yes | ||||

| DD&C | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| DN&C | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| DDC&M/O | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| D&C | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| DC&M/O | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Managing contractor | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Alliance | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| PFP | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

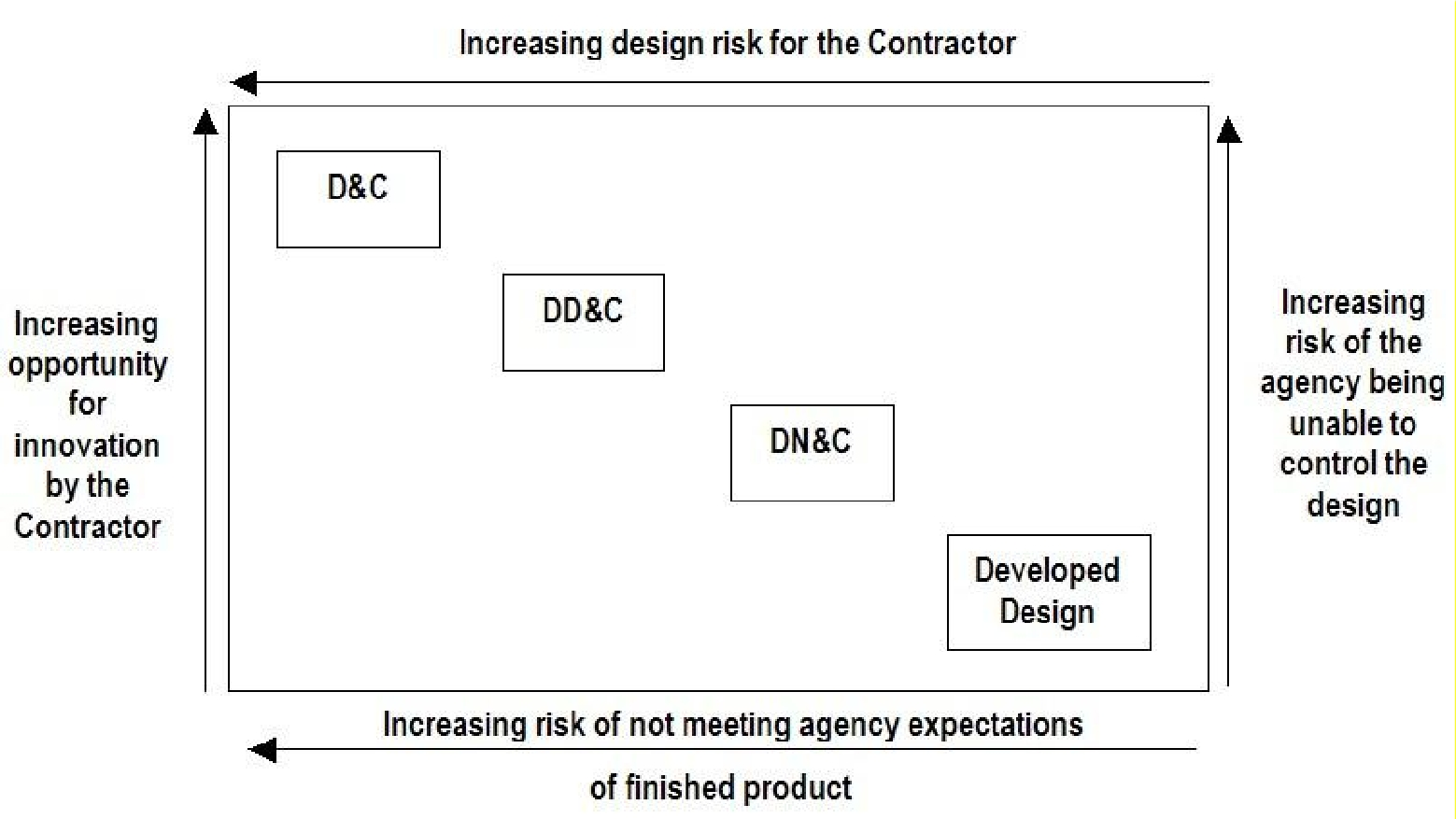

Different contractual arrangements allocate risks differently between the contracting parties.

For example, under a D&C contract the contractor accepts more design-related risk than for a developed design contract. As a result, the agency is exposed to less risk of cost increases due to documentation errors and related claims.

However, as the amount of detail provided in the tender documentation decreases, the agency relinquishes control of the design and accepts increasing risk that the completed work will not meet its expectations.

The agency may need to direct variations if its requirements are not clearly described in the tender documents, resulting in additional costs and delays.

Increasing the contractor’s design obligations is also likely to lead to:

- longer periods for tendering and tender evaluation, with associated higher costs for industry and the agency

- higher tender prices to allow for the associated risk transfer, and

- higher cost impacts if the agency requests a design change.

The major benefits of a D&C contract derive from the control the contractor can exercise over design details and the timing of the work. The contractor’s ability to introduce innovation can lead to cost savings for the agency, and design and construction activities can be overlapped in order to meet program requirements.

Figure 1 indicates how, in traditional construction contracts, the allocation of design control and design risk changes with the type of contract used.

With managing contractor and alliance contracts, the agency’s design risk can be reduced by involving the contractor in developing the project brief and scope and the detailed design.

The contractor’s design risk does not increase markedly under these contractual arrangements since payment for early development work is on a 'cost plus' basis and the target price is not agreed until the scope of work the contractor is to complete is fully understood.

Including maintenance in a contract that includes design and construction can reduce quality risks and improve value for money, as there is an extra incentive for the contractor to maintain standards in order to reduce maintenance costs.

It is important to take the relative benefits and risks into account when selecting a contract type. The information in this guide is intended to assist in the selection process.

Documented design (construct only)

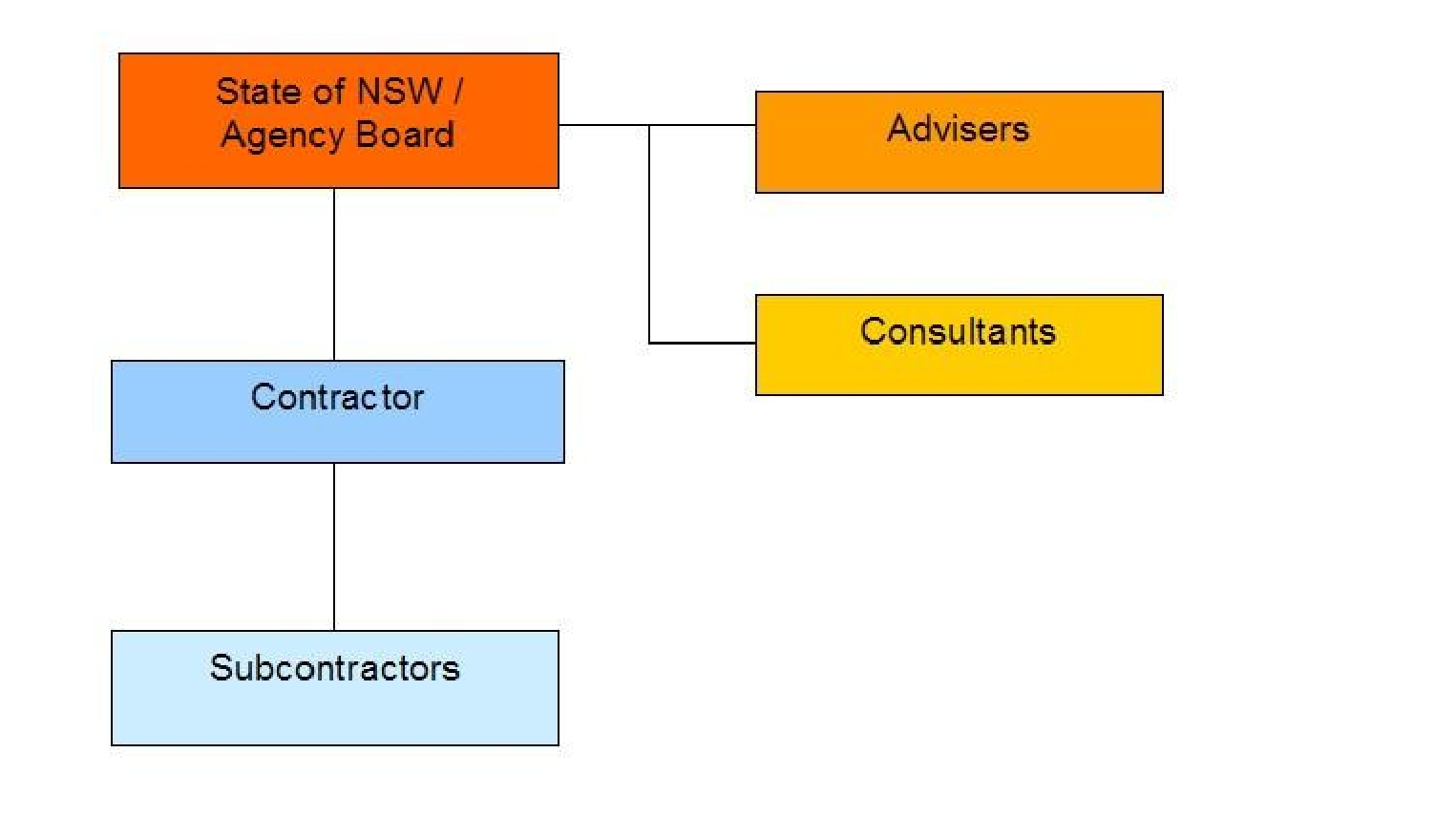

With a documented design contract, most of the design, including drawings and other design documentation, is prepared by consultants engaged by or on behalf of the agency.

Tenders for the construction contract are not called until the whole of the work is designed.

While the tender documents include detailed drawings showing the proposed work, the contractor is nevertheless required to complete the design so that it is suitable for construction. This might include determining window framing details or the locations of handrail stanchions or preparing workshop drawings for structural steelwork or air conditioning ducting.

The contractor is paid on the basis of a lump sum price or tendered rates. Additional amounts are payable for changes to the agency’s requirements, errors and omissions in the agency’s tender documentation and, usually, circumstances such as unexpected adverse site conditions.

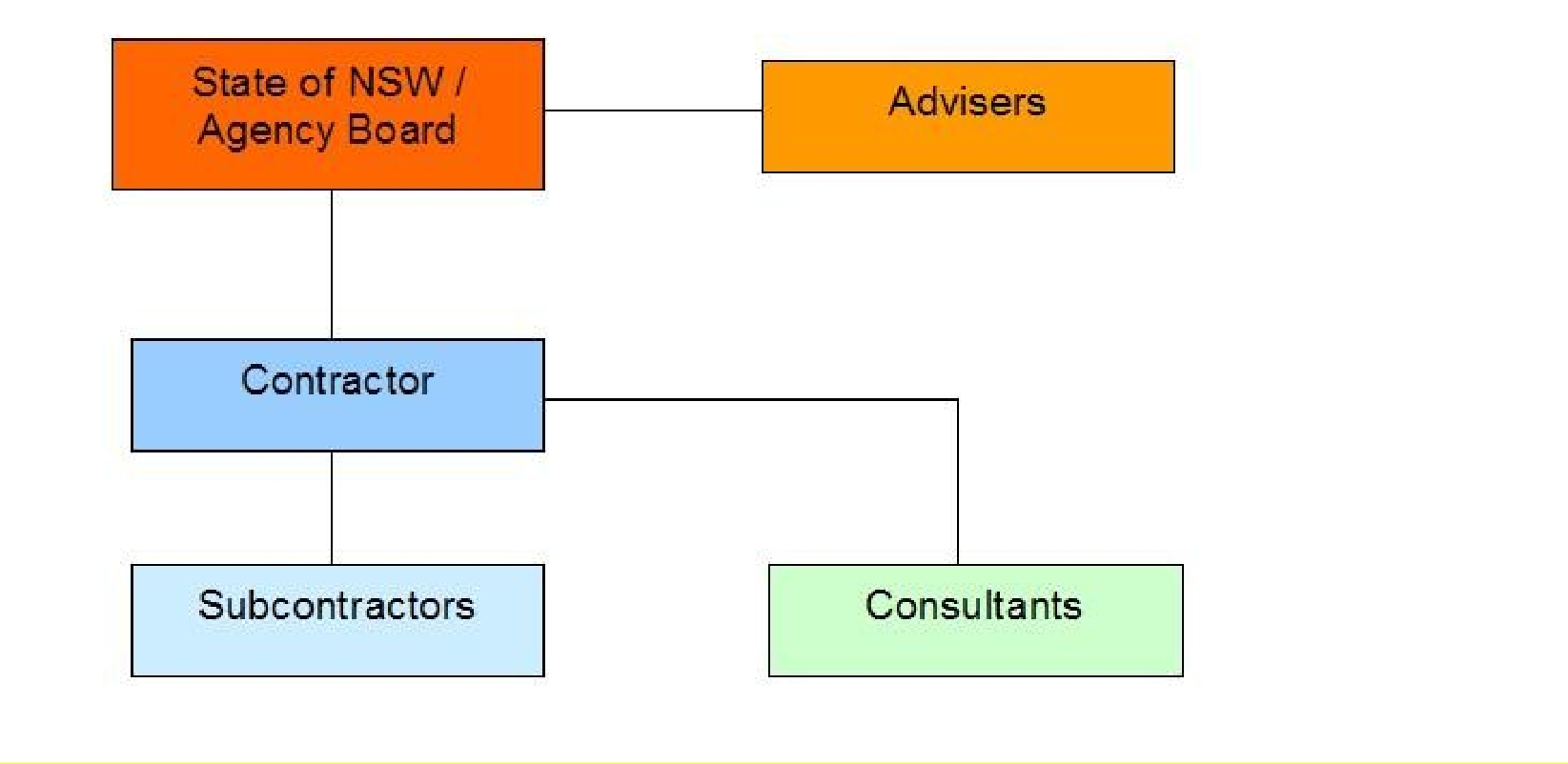

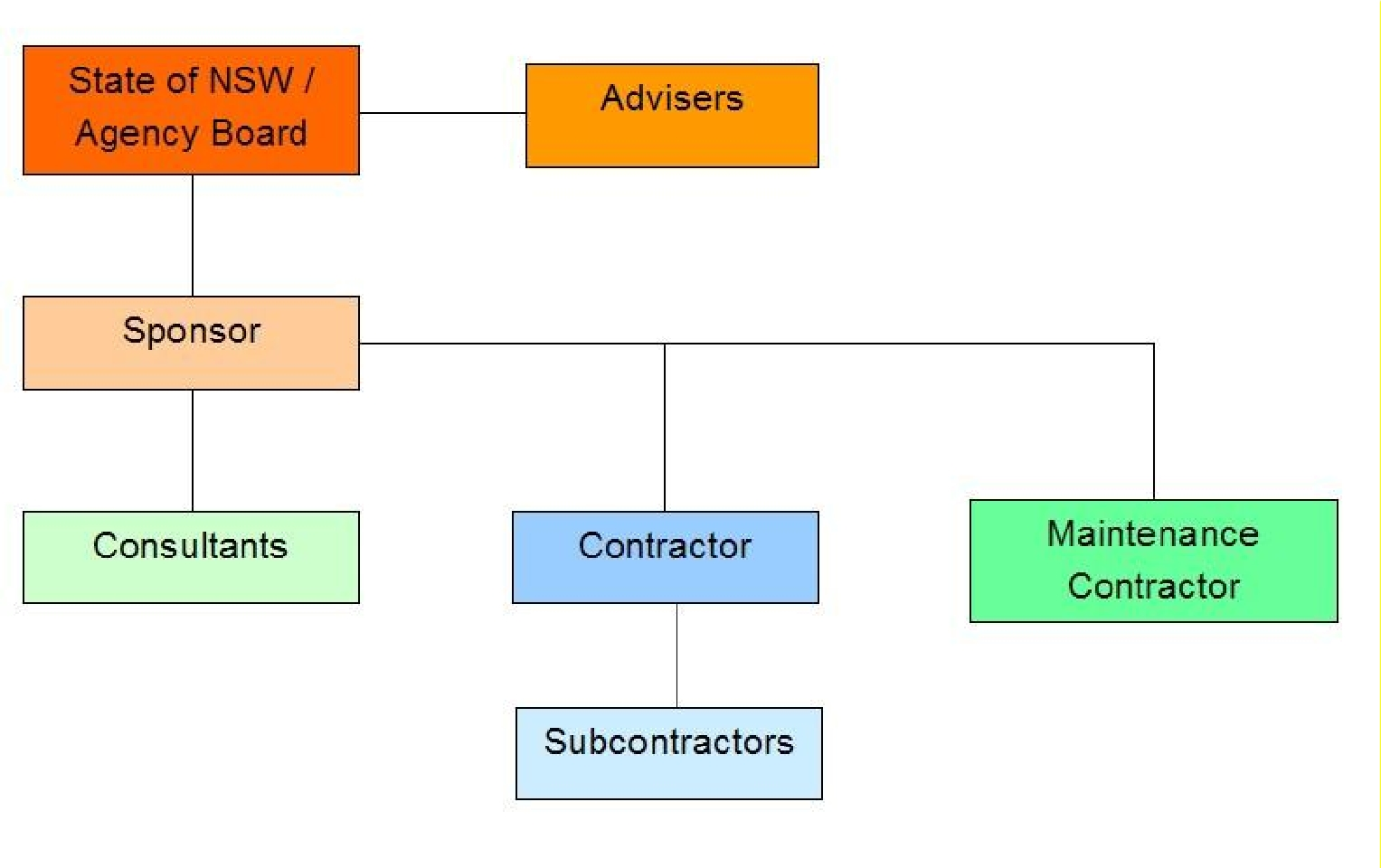

Figure 2 shows how the management approach can be represented:

A documented design contract may be appropriate for projects where:

- design quality is critical and the agency wishes to control the design process and be involved in selecting, engaging and directing the design consultants

- the agency has the skilled resources required to manage the design process

- the design parameters are likely to change as the design develops

- the optimum design can be developed without involving the prospective builder/contractor or specialist subcontractors, or

- there is enough time available within the project program for the detailed design to be completed before tenders for the work are called.

A documented design contract offers the following benefits:

- the agency maintains the maximum control over all phases of the design, and is able to ensure its requirements are incorporated

- if the agency changes its requirements during design process, the project cost increases will not include the cost of delays to the construction contractor

- tender prices do not need to allow for design or other project risks

- tendering and tender evaluation costs are relatively low

- the pool of suitable tenderers is maximised, increasing competition and the likelihood of obtaining value for money

- the contractor assumes the construction risks.

A documented design contract has the following risks:

- agency personnel have flexibility to change the project brief during the design process, which can result in additional costs or delays

- delays during design will delay the project, since construction cannot commence until the design is completed

- the volume and complexity of the tender documents increases the risk of errors and omissions that can give rise to variations and associated additional costs and delays.

Design development and construct (DD&C)

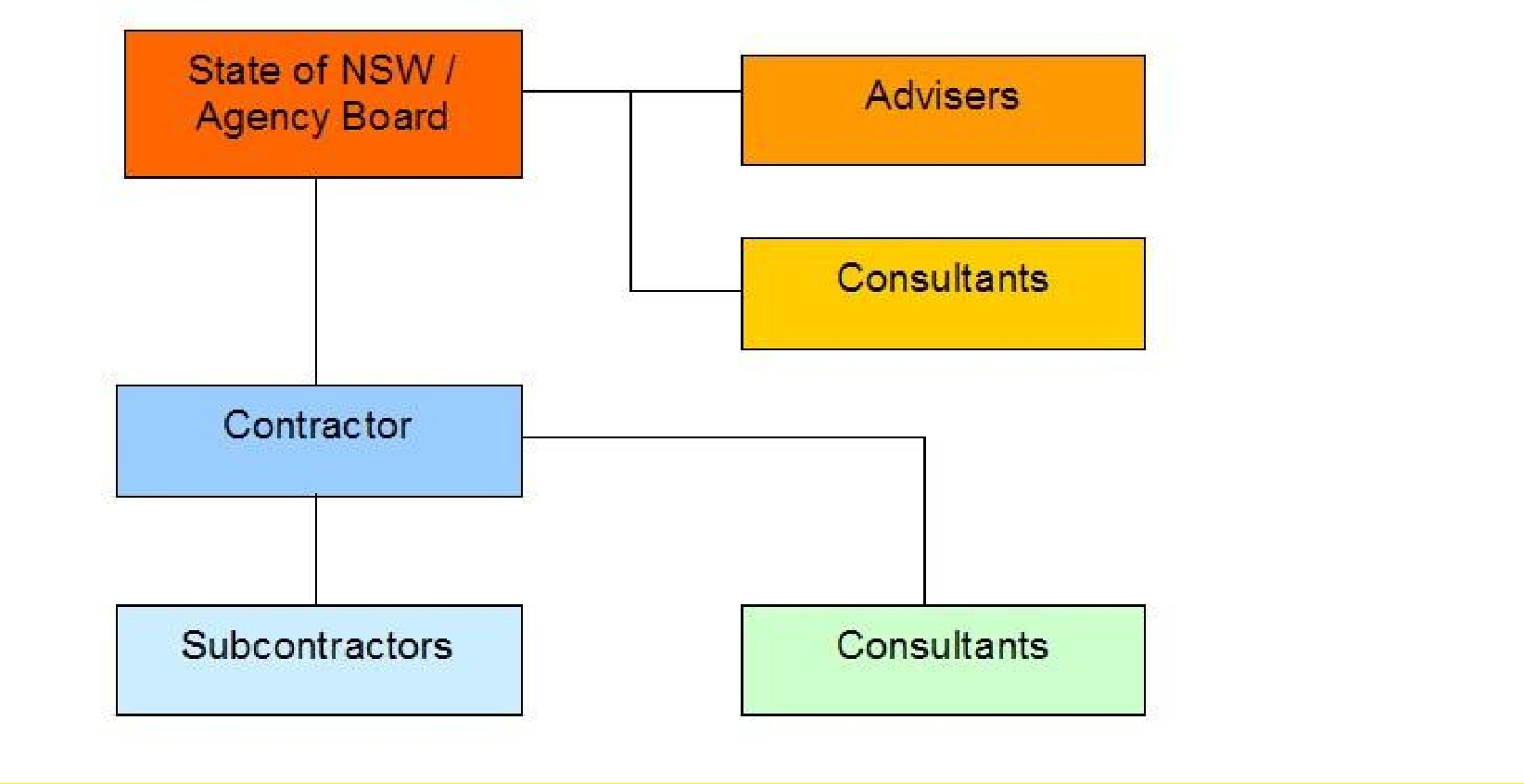

Under a design development and construct (DD&C) contract, the contractor is required to engage its own consultants to develop a preliminary design provided by the agency. The contractor prepares construction documentation and constructs the asset.

The preliminary design work, carried out by consultants under the agency’s direction, may include a concept design, a functional design or a performance specification.

The contractor is paid on the basis of a lump sum price or tendered rates. Additional amounts are paid for variations to the agency’s requirements, but because the tender documentation is not detailed, the agency is exposed to less risk on account of errors and omissions than for a developed design contract. The risk of latent conditions is generally allocated to the contractor.

Figure 3 shows how the management approach can be represented:

Projects suited to a DD&C contract are those where:

- the agency wishes to determine the concept design

- there is a significant risk of delays or changes to project scope as issues are resolved with stakeholders or investigations are completed, and the agency is best placed to manage these activities

- the requirements for the developed design can be clearly described, for example through established standards for products and materials, details and finishes

- a fully developed design would introduce risks associated with buildability or the coordination of design and construction

- there are proprietary designs or construction processes that may offer advantages over special one-off designs, or

- the agency does not have sufficient time to manage the design to completion.

A DD&C contract offers the following benefits:

- the agency is able to substantially determine the concept and functional design before a contract is awarded, reducing the likelihood of contract variations

- the contractor has flexibility to incorporate innovations and improve buildability through the design development, potentially saving costs

- the contractor assumes responsibility for the fitness for purpose of the finished product, buildability of the detailed design and usually latent conditions

- project time targets can be maintained by starting construction prior to finalisation of detailed design, if necessary, at the contractor's risk

- tender prices do not need to include allowances for the risks of performing extensive investigation work or interacting extensively with outside authorities

- the risk of contract claims due to errors and omissions in the design is reduced.

A DD&C contract has the following risks:

- if the design documents supplied by the agency are unclear or in error, the desired outcomes may not be achieved without disputes over interpretation, variations and additional expense and delays

- changes to the agency’s requirements during design development are likely to be costly, due to their potential to impact on the contractor's work and program

- tender prices are likely to be higher to allow for the contractor’s increased risk

- the number of potential competent tenderers is less and tenderer interest may be reduced due to the higher cost of tendering, resulting in higher tender prices.

Design, novate and construct (DN&C)

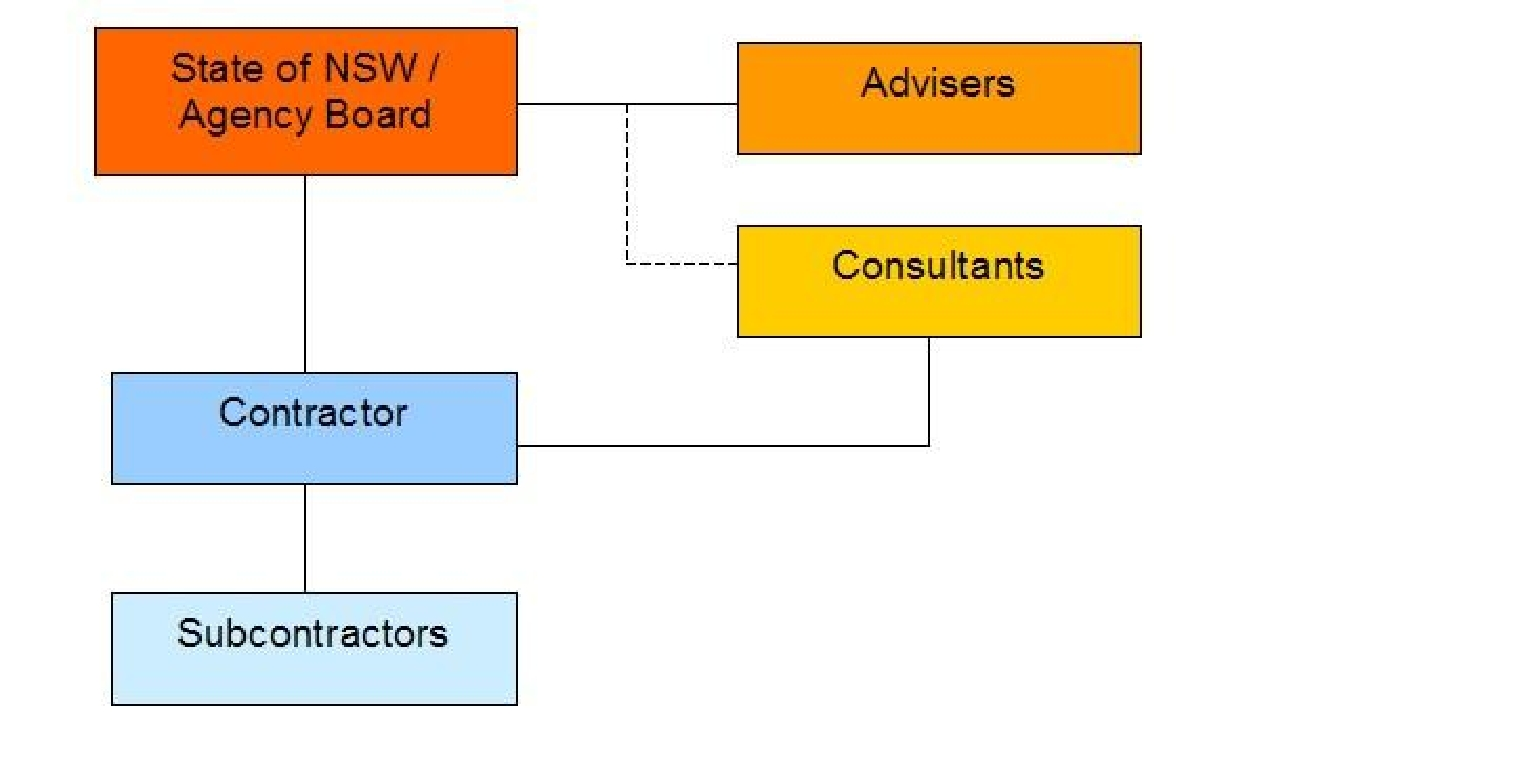

A design, novate and construct (DN&C) contract is similar to a DD&C contract. Its distinguishing feature is that a single designer or design team is used from concept design through to design completion.

The agency engages a designer to carry out early design work, under a design agreement. The agency then enters a contract with a construction contractor.

When the construction contract is let, the agency novates the design agreement to the contractor. Novation involves signing over the contractual relationship between the designer and the agency to create a contractual relationship on the same terms between the designer and the contractor.

The contractor then assumes full and unambiguous responsibility for the whole of the design as well as the construction. The contractor takes over responsibility for paying the designer's fees for work done from the time of novation.

Figure 4 shows how the management approach can be represented:

Note that both the design agreement and the construction contract must include provisions foreshadowing the planned novation to the contractor. A form of novation agreement is generally provided in the design agreement and the construction contract.

A DN&C contract is suitable where:

- the agency wishes to control the concept design

- the project has special design needs

- there is significant extra benefit in making the contractor responsible for all design and documentation, and giving the contractor full access to the original designer and its knowledge of the design issues, or

- the specification for the developed design can be clearly described, for example through established standards for products and materials, details and finishes.

A DN&C contract offers the benefits of a DD&C contract plus the following:

- there is continuity of the designer“s involvement in design and documentation, reducing the risk of the completed design not meeting the agency’s requirements.

A DN&C contract has the risks associated with a DD&C contract plus the following:

- the contractor and the designer may load their tender prices to cover the risks of entering into a contract with an unknown entity, on terms predetermined by others

- some potential service providers may be reluctant to tender

- there is potential for complex litigious problems if the relationship between designer and contractor deteriorates.

Design and construct (D&C)

For a design and construct (D&C) contract, the agency provides a project brief, which may include some concept design and specifies performance and quality requirements.

The contractor engages consultants to prepare or complete the concept design, develop the design and prepare construction documentation. The contractor may also be given responsibility for obtaining approvals from authorities.

A 'supply and install' contract can be a form of a D&C contract.

The contractor is paid on the basis of a lump sum price or tendered rates. Additional amounts are paid for variations to the agency’s requirements, but the agency bears little of the risk of errors and omissions in tender documentation, since the contractor prepares the bulk of the design and documentation. The risk of latent conditions is generally allocated to the contractor.

Figure 5 shows how the management approach can be represented:

D&C contracts are suitable for projects where:

- the agency does not wish to control the design or determine the design details

- it is unlikely that the project brief will change after the contract is entered, for example through stakeholder involvement

- the desired outcomes, project scope and performance requirements can be clearly articulated in the tender documents

- the agency has well-established standards for components, finishes and other aspects of the design

- contractors or specialist firms are expected to be able to offer proprietary systems or innovative designs or construction processes that result in cost savings and benefits for the agency, or

- there is insufficient time to produce the design required for a developed design or DD&C contract before construction work is scheduled to commence.

If the agency’s requirements cannot be clearly identified when the construction contract is entered or there are possible latent conditions or other risks, the tenders may be heavily qualified or include large contingency sums, reducing the anticipated cost advantages.

A D&C contract offers the following benefits:

- the contractual cost implications provide a disincentive for the agency to change its requirements after the contract is entered

- the contractor has flexibility to incorporate innovations, use proprietary designs and products and improve buildability, potentially improving project outcomes and increasing value for money

- the contractor can maintain project time targets by starting construction before the detailed design is finalised, if necessary, at the contractor's risk

- accurate cost forecasts can be made before design commences, on the basis of tender prices

- the risk of contract claims due to errors and omissions in the design is low

- the contractor assumes responsibility for design and construction, fitness for purpose of the finished product, buildability and usually latent conditions

- responsibility for obtaining authority approvals and meeting authority requirements can be allocated to the contractor.

A D&C contract has the following risks:

- if the tender documents are unclear or incomplete, the desired outcomes may not be achieved without disputes over interpretation, variations and additional expense and delays

- design activities are suspended during a relatively long tendering period, and progress may be delayed by complex tender reviews

- tender prices will include allowances for the additional design risks

- tender evaluation is complex and may increase costs and cause delays

- higher tendering costs and a lower number of competent tenderers may reduce competition and increase tender prices

- changes to the design requirements are likely to be costly, due to their potential to impact on the contractor's work and program.

Design, construct and maintain (DC&M)

Under a design, construct and maintain (DC&M) contract, the contractor is provided with a project brief, generally including some concept design and the quality and performance requirements of the asset are specified.

The contractor is responsible for the preparation or completion of the concept design, development of the design, preparation of construction documentation, construction of the asset and maintenance for a specified period (say 10 years).

Asset condition monitoring indicators are specified, by which the performance of the completed asset will be measured during the maintenance period.

A DDC&M contract is similar, but a larger proportion of the design is completed before awarding a contract. Maintenance can be included in a developed design contract, but will not offer the same advantages as are gained if the contractor is responsible for design or design development.

Design construct and operate (DCO) contracts and DDC&O contracts are also similar, but include a requirement for operation instead of maintenance.

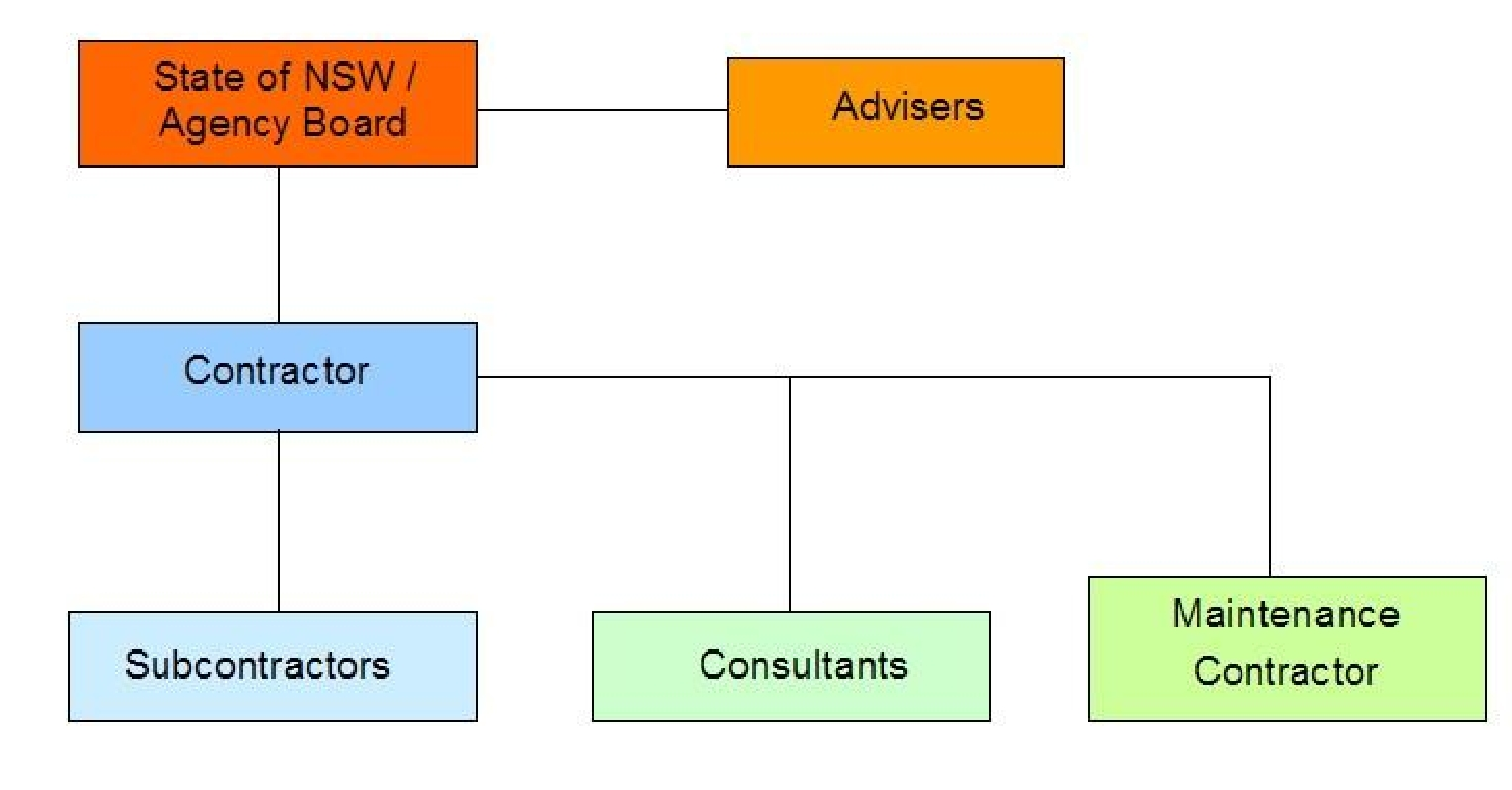

Figure 6 shows how the management approach can be represented:

Projects are suitable for DC&M contracts where they are suitable for D&C contracts (see above) and where, in addition:

- the asset will involve significant ongoing maintenance effort and costs that are directly impacted by the design and construction outcomes

- there is no advantage to be gained by the owner maintaining the asset or including it in a portfolio of assets in a separate maintenance contract, and the agency wishes to transfer the risk of routine maintenance to the contractor

- the agency has established standards for maintenance or the expertise necessary to define its maintenance requirements

- there are likely cost and other benefits to be gained from encouraging tenderers to offer alternative design concepts and maintenance ideas.

This type of contract is inappropriate if the agency’s maintenance requirements cannot be clearly described at the time of entering into a contract. It is not suitable for smaller projects.

As is the case for D&C contracts, the tenders may be heavily qualified or include large contingency sums if the contract requirements are not clearly defined, reducing the anticipated cost advantages.

It is unlikely that the construction contractor will have a maintenance capability, and a cost premium will be incurred for the contractor to establish an arrangement to meet its maintenance obligations.

A DC&M contract offers the benefits of a D&C contract plus the following:

- the contractor has an incentive to construct a higher quality product in order to minimise maintenance costs, potentially increasing value for money

- maintenance costs can be forecast before design commences

- the contractor is responsible for the fitness for purpose of the asset and the maintenance procedures, and the interfaces between design, construction and maintenance

- the contractor’s liability for defective works can be extended beyond what is normally the limit by law (6 years in NSW unless a deed is entered into).

A DC&M contract has the risks associated with a D&C contract plus the following:

- if the maintenance requirements are not clearly defined and performance measures specified, the maintenance work could be below the anticipated standards or the contractor could claim extra in order to meet those standards

- variations to maintenance requirements may be costly

- most construction contractors do not have a maintenance capability and would subcontract the maintenance activities, introducing additional administration costs and the risk of conflicts between the constructor and the maintainer

- coordination and cooperation between the contractor and the occupiers of the site may not be achieved.

Guaranteed maximum price (GMP)

Specifying a Guaranteed Maximum Price (GMP) can provide greater certainty of meeting the required project end cost and completion date. It is generally applied to a DD&C or a D&C contract.

The GMP contract is designed to limit changes to the contract price or completion date and to reduce contract management effort by incorporating terms such as:

- allocating to the contractor the risks associated with ambiguities or discrepancies in the tender documents, by allowing no claims for variations resulting from such ambiguities

- not requiring the contractor to use preferred or selected subcontractors

- including no provision for additional payment on account of latent conditions

- allowing no cost adjustment for inflation

- reducing the contractor’s entitlement to extensions of time, for example by disallowing claims on account of inclement weather or industrial disputes.

A GMP contract may include a provision requiring the contractor to provide offsets to maintain the original contract price by reducing the quality or scope of the work if the agency directs a variation. It may also allow a bonus for early completion.

Unless the agency directs a change to the scope of the project, the contractor must complete the work for the tendered lump sum price.

GMP contracts are suitable for projects where:

- it is critical that the allocated budget and time are not exceeded, and the agency is prepared to accept a higher tender price to ensure these targets are met

- the agency does not wish to control the design

- the project requirements can be defined clearly when tenders are called

- the agency is prepared, if necessary, to sacrifice project scope or quality in order to prevent time or cost growth.

A GMP contract offers the following benefits:

- there are contractual mechanisms to inhibit the end cost from exceeding the original contract price, by restricting the contractor’s entitlements

- the contractor is more likely to complete the work on time due to limited opportunity to claim extensions of time

- contract administration costs are lower due to the limited scope for claims

- agency-initiated variations that increase the scope of the work are discouraged.

A GMP contract has the following risks:

- agency expectations may not be met, if project scope or quality is reduced to meet cost or time targets

- tender prices are likely to be high, as tenderers need to price significant additional risks that may not eventuate

- tenderer interest may be limited due to the risks imposed on the contractor

- contract provisions that limit the contractor’s capacity to recoup losses may result in disputes.

Managing contractor

A managing contractor contract is generally awarded early in the design phase, after a project brief or a concept design is developed. The tender document sets a target construction sum (or target price) based on the estimated cost of the construction work and a target date or dates for completion.

The contract is awarded on the basis of non-price criteria and tendered management fees.

There are many possible variants of a managing contractor contract. Some commonly used features are described below.

The contractor undertakes a significant part of the role a project manager carries out in a more traditional procurement approach. The contractor may be required to obtain development approvals, liaise with user groups and carry out site investigations.

The contractor engages consultants to complete the design and develops a program for preparing documentation, construction, commissioning and maintenance or operation.

For this development and management work, the contractor is paid the actual costs of consultants and service providers, often based on an open book approach, and the tendered management fee. The management fee can be a lump sum or a percentage of actual costs.

During this first stage, the contractor assesses the total cost to complete the contract work, including subcontractor costs, consultant fees and its management fee.

At a time when a firm estimate of the cost is possible, the contractor is required to submit a guaranteed construction sum (GCS) for agreement, or to confirm that the work can be completed for the target construction sum.

The GCS must not be greater than the target construction sum, and the contractor may be entitled to an incentive payment if the GCS is less than the target construction sum.

The contract may include an option to test the market, on the basis of completed designs, and elect not to accept the contractor’s GCS.

If the GCS is accepted, the contractor completes the construction documentation and manages the work covered by the GCS, including construction, commissioning and maintenance/operation if required. The contractor may choose to achieve the target completion dates by commencing early construction works before the design is completed.

The agency may direct variations to the work after the GCS is accepted, but if it does, it must adjust the GCS accordingly. The contractor warrants that the GCS (as adjusted for the principal’s variations) will not be exceeded.

The contractor is paid the actual costs incurred for materials, subcontracts and consultancy agreements plus its management fee, up to the GCS. If the GCS is exceeded, then the contractor is required to meet the additional costs.

To provide an incentive to manage the costs, the contractor is also entitled to share any cost savings upon completion and is commonly paid 50% of the difference between the actual costs plus its fees (the actual construction sum) and the GCS.

The potential for incentive fees to be earned is the most important aspect of the management contractor contract. It encourages the contractor to be efficient and make whatever savings are available. Other incentives linking aspects of performance to additional payments can also be incorporated into the contract.

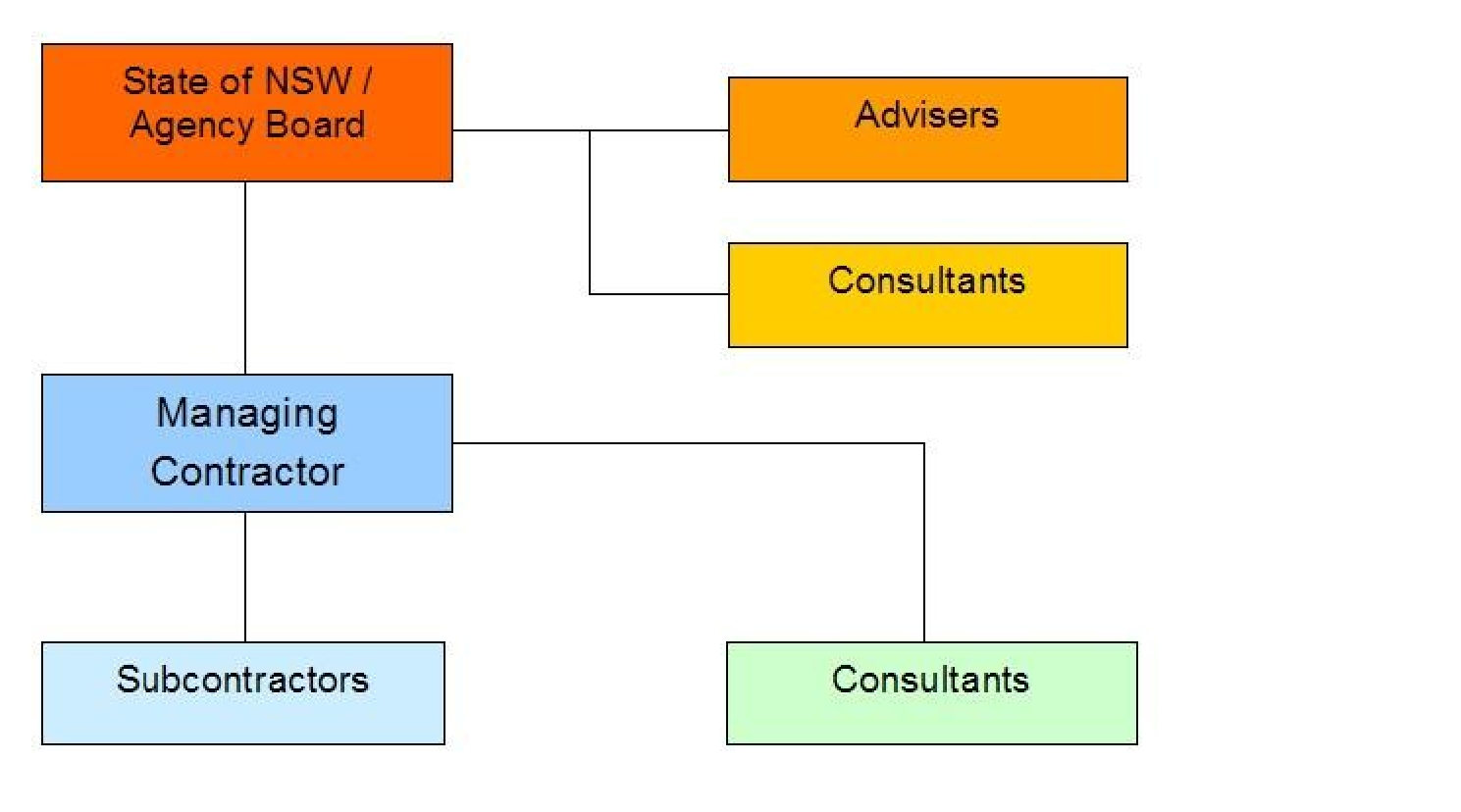

Figure 7 shows how the management approach can be represented:

Managing contractor contracts are only warranted for major projects with special needs, such as those where:

- there are many or significant unknown factors, such as undefined scope, unpredictable risks and changeable project objectives, that cannot be resolved before it is necessary to let a contract in order to meet the project program

- project threats and opportunities are complex and require management collectively by the contracting parties and other participants

- there are many complex or difficult stakeholder interfaces and relationships

- the interests of key participants need to be brought together early in the project

- industry input and innovation during the design stage are desirable, for example to take advantage of emerging technology, specialist construction expertise or other opportunities

- completion times are tight and fixed

- project funding is fixed.

A managing contractor contract offers the following benefits:

- the agency and the contractor work together to determine project requirements, resolve issues and develop the design, reducing the risk that the agency’s requirements will not be met and promoting optimum design outcomes

- *involvement of the contractor and stakeholders in design decisions facilitates the development of appropriate responses to the project objectives

- the agency controls the design and can make changes without incurring the disproportionate additional costs, including delay costs, likely with a D&C or DD&C contract

- the contractor assists the agency to control the costs during the design phase

- once a GCS is agreed, the contractor will not be paid more unless the agency directs a variation

- the contract includes incentives for the contractor to make cost savings

- design activities can continue during the tender process, minimising delays

- it is possible to commence construction before the design is completed, normally once the GCS is agreed

- the need for separate project management services is reduced, since the contractor undertakes most project management functions

- the tender prices need not allow for as much risk as for a D&C contract

- tendering costs are low since tenders include only fees and non-price information

- the contractor is responsible for design/construction interface risks and coordination of all subcontractors and consultants

- the contract can incorporate non-adversarial mechanisms for resolving differences efficiently, such as the establishment of a dispute resolution board.

A managing contractor contract has the following risks:

- success depends on cooperative relationships and the contractor efficiently managing project risks and controlling costs

- to achieve the optimum cost control, the agency must be prepared to amend its requirements if the contractor identifies a cost increase

- design development work is paid on a 'cost plus' basis and the contractor has little incentive to expedite progress in the early stages

- contract administration is complex and requires more agency resources in the early stages to establish the project scope and objectives

- margins on the cost of the work are likely to be high

- target prices set at the outset, when the scope of the work is uncertain, may not be achievable

- the GCS is set without competition and may not offer value for money

- the agency’s expectations may be unrealistic and agreement on a GCS or time targets may not be reached, leading to termination of the contract and significant time delays

- the number of willing and competent tenderers is limited.

Alliance

An alliance contract (or project alliance) is an agreement between 2 or more entities that undertake to work cooperatively, reaching decisions jointly by consensus and using intensive relationship facilitation. The entities work together to achieve agreed outcomes and share project risks and rewards, relying on good faith and trust.

An alliance is a relationship contract that seeks to turn a project into a joint venture, where everyone involved is effectively treated as a member of the joint venture company.

The contract includes processes to manage relationships, remove barriers and maximise the contributions of all the participants. It requires the parties to commit to common objectives, act cooperatively, make decisions collectively, share information and knowledge and adopt a non-adversarial attitude to resolving differences.

Alliance participants vary to suit the project and are selected early in the project on the basis of non-price factors that will assist in delivering the required outcomes. Typically they include designers, consultants, management service providers, suppliers and construction contractors.

All the parties involved in a project could be alliance participants, or some parties could be engaged through more conventional contracting arrangements.

An alliance agreement includes conditions developed by the participants, generally under interim 'cost plus' consultancy agreements with the funding agency. Participants are represented on a management 'board' with an equal say in decisions made by consensus.

The people provided by the participants have defined roles and responsibilities in an integrated management team, and decisions are made on a best-for-project basis.

An alliance contract would usually require early identification of a target cost for the whole of the project, with actual project costs to be within the target cost and losses and gains, risks and rewards to be shared.

The alliance participants are normally paid their base costs, confirmed by open-book audit or negotiation, plus agreed corporate overhead and profit margins, as long as the target cost for the project is not exceeded and target performance is achieved.

If targets are not achieved, the margins are reduced according to agreed formulas. Other incentives may also be linked to performance targets, such as the payment of agreed shares of savings or the deduction from payments of agreed shares of cost overruns.

The liability of non-agency participants would generally be capped, with the agency accepting the remaining liability. The participants adopt a no-blame culture and litigation is only available for wilful default such as non-payment or failing to maintain insurance, honour an indemnity or provide audit access.

The agency has the right to change the project parameters, including project scope, budget and time, and the participants must change the Agreement to suit. The agency may also terminate the agreement, for example if consensus cannot be reached on a decision.

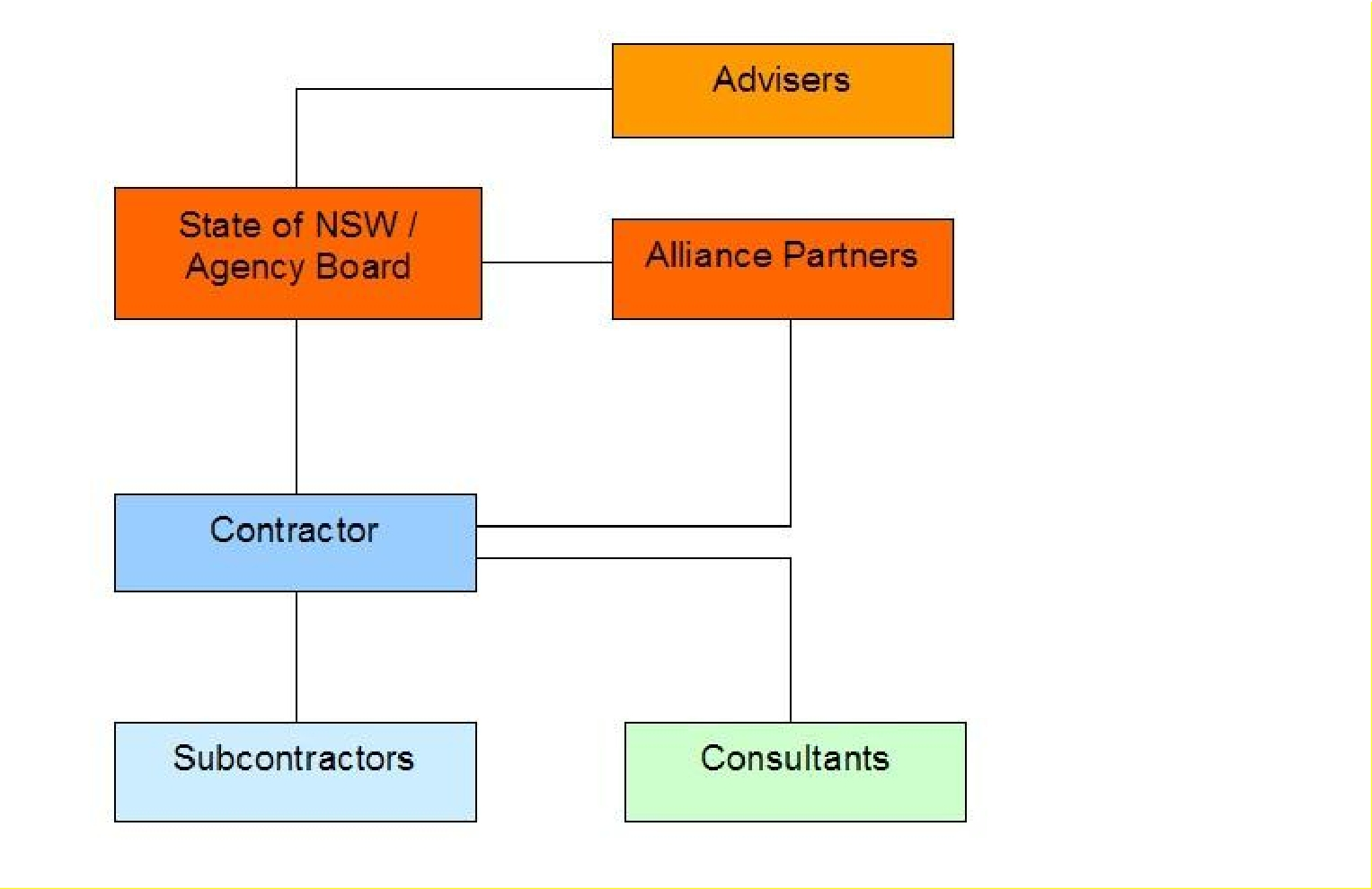

Figure 8 shows how the management approach can be represented:

Alliance contracts may be beneficial for complex projects of moderately long duration (greater than 12 months) with some or all of the following characteristics:

- unclear or uncertain scope, unknown factors, unpredictable risks or changeable project criteria

- threats and opportunities that are best managed collectively by the participants, rather than allocating them to a single party

- a requirement for early input from a range of stakeholders, including end users

- exceptionally challenging issues requiring special stakeholder and community involvement

- particularly difficult and complex stakeholder, consultant and contractor interfaces and relationships requiring a special management approach

- a need for early advice from construction industry experts to help define the project scope and resolve issues

- a high profile and a requirement to achieve extraordinary outcomes under extraordinary circumstances

- limited time to resolve issues and define the project scope

- a fixed and limited budget

- willingness on the part of the agency to participate in a relationship contract.

With other contract arrangements, these factors would place project outcomes at risk and provide more potential for claims and disputes.

An alliance contract will not be suitable if:

- the personnel involved (from the agency and other stakeholders, consultants and contractors) are not experienced at working together and unwilling or unable to adopt the attitudes and corporate cultures necessary to work as a team

- the agency is not prepare to invest the resources required to participate in a relationship contract and accept a risk sharing arrangement

- the project is relatively small, and the additional tendering and implementation costs are disproportionate with the cost of the work and the likely benefits, or

- more conventional contracts will achieve the outcomes required, since the project is not complex or there is little room for improving outcomes or issues can be resolved without contractor involvement early in the design process.

An alliance contract offers the following benefits:

- there is potential for reduced project costs, earlier completion and better outcomes in general, for special projects under extraordinary circumstances, through incentives for cost savings, cooperation and relationship management

- involvement of the contractor and stakeholders in design decisions facilitates the development of appropriate responses to the project objectives, providing potential for innovation to improve outcomes

- there is more certainty and less risk for non-agency participants

- fast-tracking of the project is possible

- issues that could cause claims and disputes are more likely to be resolved in the manner that is best for the project.

An alliance contract has the following risks:

- success depends on teamwork and the adaptability, performance and attitudes of individuals

- there are more demands on all personnel involved, and a change in culture and attitude may be required for many

- non-agency participants are required to make extra effort to achieve stretch goals, manage changes to culture and attitudes, set up accounts open to public scrutiny and commit the best people to one project

- non-agency participants expect and receive a substantially higher margin (including profit) for the additional input required

- more agency resources and higher costs are involved to manage tendering processes, establish the alliance, maintain relationships and determine costs

- quality can be compromised to meet cost targets

- risk allocation may not be clear, and the agency bears the risks once the specified liability of other participants is exceeded

- there is less price competition and less certainty of obtaining value for money

- consultant costs for project development and design are likely to be higher

- the agency loses some litigation rights, and reduced professional indemnity insurance cover is provided by the participants.

Privately financed project (PFP)

Under a privately funded project (PFP), the private sector finances and constructs a capital asset, then owns and usually operates the asset for a specified period. NSW Government may contribute to the project by providing land or capital works, accepting some risk, diverting revenue or purchasing agreed services such as operation and maintenance of the asset.

The approach is used to provide new infrastructure assets and deliver associated services for a period that is typically around 25 years. Some examples or PFPs are:

- build, own, operate, transfer (BOOT) scheme

- build, own, transfer (BOT) scheme

- design, build, finance and maintain (DBFM) scheme.

PFP arrangements are complex because of the financial component of the contract and are not suited to all projects.

The NSW Treasury publication Working with Government: Guidelines for Privately Financed Projects, available on the NSW Treasury website, describes the mechanism used by NSW Government to involve the private sector in the procurement of infrastructure using PFP options.

The guidelines provide information and guidance on:

- identifying PFP options

- the PFP development and approval process

- the project management structure

- disclosure requirements and project reviews

- risk management

- assessing PFP offers

- probity and accountability

- terms the contract should include.

A PFP involves a 2-stage tendering process. Expressions of interest are called and assessed to establish a shortlist of suitable proponents. This is followed by a call for detailed proposals and further assessment of the benefits offered. The contracts are complex and may take considerable time and effort, including legal advice, to negotiate.

A PFP should offer a financial advantage to the State, in particular in relation to initial capital investment.

Figure 9 shows how the management approach can be represented:

A PFP is suitable for projects where:

- the total contract value is $50 million or more

- the contract involves a long service delivery period, typically 25 years or more

- the required services can be specified in terms of measurable performance outputs

- a return can be provided to a private sector developer, for example over a concession or service delivery period

- the overall outcome for NSW Government can be shown (using comparator model assessments) to be better than for other procurement methods

- the benefits warrant the cost, time and resources required to develop tender documents and evaluate proposals, including implementing comparator assessments.

A PFP contract offers the following benefits:

- the impact of obtaining capital funding can be either totally or partially absorbed by the private sector, or spread over a much longer period than if the project were publicly funded

- asset development and, where applicable, associated service provision can be more efficient and economical when a single entity is responsible

- there are opportunities and incentives for the contractor to develop innovative solutions

- asset management considerations can influence the design and construction, resulting in improved service delivery

- design, construction and commissioning risks, including timing risks, can be allocated to the private sector

- agency resource requirements and costs are lower for construction of the asset

- asset management risk is allocated to the private sector developer during the maintenance or operation period of the asset

- where the responsibility for the day-to-day operation of the asset rests with the developer, the agency will most likely only be required to manage the asset lease and monitor asset management and operation.

A PFP contract has the following risks:

- public misconceptions about the benefits of private sector initiatives over Government initiatives may have to be overcome

- specialist contractual experience is needed to assess financial/technical proposals, manage the negotiations with potential developers and document and manage the PFP agreement

- the time and cost involved in negotiating a contract may be high

- tenderer interest may be limited due to the high cost of tendering

- the quality of the finished product and the services may be compromised unless quality requirements and provisions for confirming performance of the services are clearly documented

- it may be difficult to demonstrate the real relative cost benefits

- the agency loses some control of operation of the asset and possibly service quality

- the agency loses control of the interfaces with other government services

- if the project fails financially, the agency will be required to provide the services through alternative means

- changes to legislation and government policy can affect the project, and are more likely to occur due to the long contract period involved.

Related resources

Find more resources on the construction category page.