Direct Dealing Guidelines

Preface

The NSW Government is continually seeking to create value and leverage unique and innovative ideas, projects and initiatives that provide tangible benefits for the people of NSW. To achieve this, it delivers projects, goods and services using a range of methods.

Direct dealing is one such process that NSW Government may use where a competitive tender is not possible or appropriate.

Direct dealing may also be referred to as sole source or direct negotiations and is known as a type of complex market engagement method under the NSW Procurement Policy Framework.

Although direct dealing should not be routinely used as a substitute for competitive procurement processes, NSW Government may have compelling reasons for direct dealing.

For example, direct dealing may be appropriate where a counterparty is in a unique position to offer a solution that cannot be offered by competitors, or a public project or acquisition needs to interface with an existing piece of equipment, technology or facility (see section 1.1 for further detail of potentially appropriate reasons for direct dealing).

Direct deals vary in size, scope, value, significance and risk ranging from unsolicited proposals for large infrastructure projects with capital values in the order of billions of dollars, down to small transactions where the value of the transaction may be less than the cost of conducting a competitive process, such as for the purchase of emergency supplies.

Due to the varied nature of direct deals, there is no ‘one size fits all’ process or governance approach that is necessarily appropriate to apply in all direct dealings.

Nevertheless, due to the risks that may arise with direct dealing, government agencies need to have appropriate processes in place to ensure:

- direct deals deliver value for the State

- direct deals meet legal obligations under the Public Works and Procurement Act 1912

- fundamental principles of probity and the ICAC’s guidelines on direct dealing Direct Negotiations: Guidelines for Managing Risks (PDF) are complied with.

The purpose of these guidelines is to assist agencies and industry by providing a robust, consistent and transparent framework for direct dealing, where it is appropriate.

The guidelines are not enforceable and it is not mandatory for agencies to comply with the framework set out in this document, although this is recommended to ensure consistency and best practice.

To this end, the guidelines present an overarching framework for direct dealing across NSW Government agencies, setting out:

- guiding principles for direct dealing

- legal duties arising from Australia’s obligation under international procurement agreements

- core requirements that should be satisfied for all direct deals

- guidance on a best practice direct dealing process that aligns with the guiding principles and core requirements, and that agencies can use to ensure they comply with these guidelines.

The guidelines are intended to sit above other agency-specific direct dealing frameworks to ensure agencies meet key probity requirements and deliver value for the State.

The guidelines are nevertheless intended to be consistent with existing agency-specific direct dealing frameworks where possible. If agencies are uncertain regarding how their frameworks align with these guidelines, they can seek advice from Investment NSW.

Agencies should also seek advice from Investment NSW where they are uncertain on the processes or governance framework that should be applied for any particular direct deal.

The examples in these guidelines are illustrative, and in all cases agencies should consider the specific circumstances of any potential direct deal when putting in place a governance framework and, where necessary, seek advice from Investment NSW or an independent probity advisor.

Furthermore, while these guidelines are consistent with the ICAC guidelines, the obligation remains on agencies to ensure all direct deals comply with:

- the ICAC guidelines

- PBD 2019-05 Enforceable Procurement Provisions (which provides the legal framework for procurements covered by international trade agreements including the WTO GPA)

- these guidelines

- all applicable legal, policy and probity obligations.

1. Application

1.1 What direct dealing is

‘Direct dealing’, which may be solicited or unsolicited by government, refers to exclusive dealings between a government agency and non-government sector body over a commercial proposition or proposal.

It may include a limited tender conducted in accordance with the EPP Direction and the Public Works and Procurement Act 1912.

A ‘direct deal’ refers to any binding agreement reached as a result of direct dealing.

While direct dealing should not be routinely undertaken as a substitute for competitive procurement practices, there may be circumstances where it is appropriate for government to direct deal with an organisation to deliver a project, asset or service without first undertaking a competitive process.

The ICAC guidelines set out some of these circumstances, including:

- where a counterparty is in a unique position to offer a solution that cannot be offered by competitors

- when it is beyond doubt that there is only one counterparty that can meet an agency’s well-defined needs

- where intellectual property forms a necessary part of a project and ownership of that property can be demonstrated

- if a counterparty owns a parcel of real property that is on, or near, the site of a proposed project, and the land is necessary to the project

- when a public project or acquisition needs to interface with an existing piece of equipment, technology or facility and there are is no reasonable alternative or substitute

- transactions that derive from an earlier competitive process

- to avoid damaging the public interest

- emergency circumstances where a delay would threaten public health and safety, damage the environment or create a serious legal or financial risk to the agency or the government*

- when the value of the contract or transaction is very low relative to the cost of conducting a competitive process and, in the case of a covered procurement, is below the EPP Direction thresholds

- when a legitimate and recently completed competitive process has failed to produce a compliant offer, or the offers received do not demonstrate value for money, and the agency does not expect a repeat of the process to produce a better result

- when it is necessary to maintain a temporary source of supply while a planned competitive process is yet to be finalised, except if the temporary measure qualifies as a covered procurement under the EPP Direction

- a sponsorship offer may not be amenable to market testing

- where a counterparty has some form of legal right to direct negotiations.

(*) Where a direct deal is used for emergency procurements under cl. 4 of the Public Works and Procurement Regulation 2019, the government agency head or their nominee may authorise the procurement of goods and services to a value sufficient to meet the immediate needs of the particular emergency. Emergency procurements must be reported to the Procurement Board as soon as possible.

If an agency direct deal relates to a procurement covered by the EPP Direction then the agency must ensure they satisfy the requirements for limited tendering under the EPP Direction.

1.2 When to apply the direct dealing guidelines

The NSW Procurement Policy Framework should be considered as a first point of reference for all procurement matters.

In addition to the NSW Procurement Policy Framework, these guidelines should be referred to where the NSW Government is considering initiating a direct deal with a non-government counterparty.

The guidelines are not intended to apply in relation to direct dealing involving:

- negotiation of interface or access agreements

- amendments/variations of the existing legal agreements

- settlement of disputes

- acquisition of property by government at market value, or

- elements of an approved procurement method that may involve a direct dealing (such as an early contractor involvement procurement model).

In these businesses as usual scenarios, the agency’s policies and procedures should apply, as well as the ICAC guidelines and any applicable legal requirements.

The NSW Government Unsolicited proposals: Guide for Submission and Assessment, which falls under these guidelines, remain the key policy that agencies should refer to for guidance on the process by which a non-government counterparty can bring forward a proposal to government.

While these guidelines are intended to provide an overarching framework for direct dealing across NSW Government agencies, they are nevertheless intended to be consistent with existing agency-specific direct dealing frameworks where possible.

Should agencies require further clarification of the interaction between the guidelines and agency-specific frameworks, Investment NSW is available to provide advice (see section 1.5 for contact details).

Any agency-specific direct dealing framework should also consider relevant processes and approval requirements in procurement policy documents (for example, NSW Procurement Policy Framework, NSW Public Private Partnership Guidelines, NSW Business Case Guidelines, TfNSW Asset Standards Authority processes and procurement policies) or assurance processes such as:

- Infrastructure NSW’s Infrastructure Investor Assurance Framework

- NSW Treasury’s Recruitment Expenditure Assurance Framework, or

- Department of Customer Services ICT Assurance Framework.

Where a proposal requires a statutory planning decision it is the responsibility of the counterparty to secure all relevant planning approvals. Statutory planning decisions are not covered by this process.

These guidelines are not intended to absolve agencies of any existing legal requirements.

Agencies should be aware of their legal obligations under the Public Works and Procurement Act 1912 and the EPP Direction.

1.3 The approach to these guidelines

As direct deals range in size and complexity, these guidelines aim to provide robust guidance for all government-initiated direct dealing while recognising that a ‘one size fits all’ approach may not be possible.

The guidelines therefore seek to assist agencies by identifying the core requirements that all agencies are strongly encouraged to satisfy when direct dealing, whilst affording agencies discretion with how they implement those requirements into their procurement processes according to the circumstances of any particular direct deal and the guiding principles identified in this document.

To this end, the guidelines provide 3 key components of advice, explained below:

Guiding principles for direct dealing

Recognising that a ‘one size fits all’ approach is not possible for direct dealing, the guiding principles, set out in section 2, are intended to assist agencies by providing principles to guide agency decision-making regarding the processes they implement to govern direct dealing.

Where agencies are uncertain as to the appropriate processes for direct dealing agencies should have regard to the guiding principles and, where necessary, contact Investment NSW for further advice.

Core requirements for direct dealing

The core requirements, set out at section 3, identify the requirements that all agencies should satisfy for every direct deal to ensure they deliver value to the State and comply with key probity obligations. These include:

- a record of the justification for direct dealing (in the event of a direct deal regarding procurement, agencies should always ensure there is a record of the value and type of goods and services procured)

- a robust and fit for purpose governance framework, including a risk assessment and risk management strategy

- a comprehensive evaluation of the direct deal prior to acceptance by government

- appropriate approvals for key decisions.

Agencies continue to have discretion regarding implementation of the core requirements according to the particular circumstances of the direct deal and the agencies’ own procurement processes.

Best practice guidance

Section 4 sets out best practice guidance on a potential structured approach that agencies can use to ensure their direct dealing processes satisfy the core requirements and relevant probity obligations.

Section 5 and section 6 complement this process by setting out best practice guidance on evaluation and governance.

The best practice guidance may not be appropriate to implement for all direct deals. However, it is recommended that agencies use the best practice guidance as a starting point and only deviate where they are able to provide robust justification for doing so.

1.4 How direct dealing guidelines interact with government investment decision-making

In some cases, direct deals may require a funding contribution from NSW Government to deliver part of the project. This scenario is more likely to arise when the direct deal is of significant scale and has interfaces with, or delivers, a component of NSW Government infrastructure.

Where state funding is required as part of the project, a business case may be needed (in line with standard government process for securing investment decisions for state projects).

Any project that forms a component of a broader direct deal, but will be delivered using State Government funding, is required to adhere to existing government policy guidance including NSW Treasury’s Business Case Guidelines (TPP18-06) and assurance processes such as:

- Infrastructure NSW Infrastructure Investor Assurance Framework

- NSW Treasury's Recurrent Expenditure Assurance Framework, or

- ICT Assurance Framework.

A counterparty made a proposal to NSW Government to deliver a significant piece of transport infrastructure, which has already been identified by NSW Government as a strategic objective.

The offer allowed government to meet this strategic objective with significantly reduced cost to government.

To take advantage of the opportunity, government decided to concurrently run a business case process for the components of the project to be delivered by the State.

Under this arrangement, the component being delivered by government was covered by the usual Infrastructure NSW Business Case Framework and Infrastructure Investor Assurance Framework.

This provided government with the necessary benchmarking and assurance review to take advantage of the opportunity presented to it by a counterparty ensuring value for money for the people of NSW.

1.5 Contact details and lodgement

Agencies with enquiries about direct dealing should address any questions to Investment NSW at directdeals@investment.nsw.gov.au

2. Guiding principles

2.1 Overview

This section outlines the guiding principles agencies should have regard to when direct dealing.

The guiding principles reflect key established probity and governance principles that seek to ensure government:

- delivers value for the people of NSW

- conducts its commercial dealings with integrity

- direct dealing processes are fair, open and demonstrate the highest levels of probity consistent with the public interest and comply with applicable legal obligations.

2.2 Enabling government to achieve a strategic objective

As with all procurement processes and commercial transactions, agencies should have a clear vision regarding the strategic objectives and outcomes they are seeking to achieve through direct dealing.

These strategic objectives should be clearly identified and documented prior to considering direct dealing.

Agencies should continually refer to those strategic objectives throughout the direct dealing process to ensure they are delivering value for the people of NSW, and that the transaction is meeting government’s objectives.

2.3 A robust justification for direct dealing

As direct dealing should not be a substitute for regular procurement processes, it is critical that a robust justification for direct dealing is established.

While the justification may vary depending on the nature of the direct deal, agencies should establish how the circumstances of the potential direct deal:

- justify entering into exclusive negotiations

- complies with relevant legal obligations including those under the EPP Direction and Public Works and Procurement Act 1912

- may enable the government to achieve its identified objectives.

The justification for considering direct dealing should be documented and approved at an appropriately senior level prior to entering any informal or formal discussions with a counterparty.

The key practical factors that should be considered in any justification are outlined in section 3.2.

2.4 Maintaining impartiality

Due to the potential risks associated with direct dealing, fair and impartial treatment is an essential feature of the direct dealing process.

In general, the process should include a clearly defined separation of duties and personnel between the negotiation, assessment and approval functions.

Maintaining impartiality in this way will enable the fair and robust assessment of proposals and will provide the participants with confidence in the integrity of the process.

2.5 Maintaining accountability and transparency

Accountability requires that all participants acknowledge and take responsibility for their actions in decision-making and are held accountable to the people of NSW, ensuring that decisions are in the community’s best interest.

To ensure accountability, the assessment and negotiation process should identify responsibilities, provide feedback mechanisms and require that all activities and decision making be appropriately documented.

Transparency refers to the preparedness to open a project and its processes to scrutiny, debate and possible criticism. This involves providing documented reasons for all decisions taken, including the decisions to enter into direct negotiations and to enter into any agreements or binding documentation with any counterparties.

Appropriate information should also be provided to relevant stakeholders.

In accordance with these principles and with the State’s obligations in relation to the Government Information (Public Access) Act 2009 (GIPA Act), relevant summary information regarding a direct deal and its assessment may need to be published and made publicly available.

If an agencies' direct deal relates to a procurement covered by the EPP Direction then the agency must ensure that they satisfy the requirements of the EPP Direction.

2.6 Managing conflicts of interest

In support of the public interest, transparency and accountability, NSW Government requires the identification, management and monitoring of real, perceived and potential conflicts of interest.

Participants will be required to disclose any current or past relationships or connections that may unfairly influence or be seen to unfairly influence the integrity of the assessment process.

2.7 Maintaining confidentiality

In addition to requiring high levels of accountability and transparency, direct dealing may require some information to be kept confidential, at least for a specified period.

Any potential direct deal will generally be kept confidential until the signing of an initial process document, such as a memorandum of understanding or similar document between government and the counterparty.

In some circumstances, it may also be appropriate to keep a direct deal confidential until the signing of binding documentation. This is important to provide participants with confidence in the integrity of the process.

Notwithstanding the above, there may be circumstances where legal or regulatory obligations require an agency to provide information about the direct deal to a third party, such as obligations arising from the GIPA Act or EPP Direction. Agencies should seek legal advice if information is requested under such provisions.

2.8 Obtaining value for money

Obtaining optimal value for money is a fundamental principle of public sector work. This is achieved by:

- ensuring that robust processes are in place to maximise government’s capacity for negotiation

- undertaking comprehensive evaluation prior to government making any binding commitments to proceed with the direct deal.

Ensuring value for money is achieved will generally require that government evaluates the financial and non-financial costs and benefits of a clear commercial proposition from a counterparty prior to making any binding commitments.

Assessing value for money requires a balanced assessment of a range of financial and non-financial factors, such as:

- quality

- cost

- fitness for purpose

- capability

- capacity

- risk

- total cost of ownership

- environmental sustainability

- other factors the agency considers relevant to the procurement.

In undertaking discussions relating to a proposal for the purchase of government assets, government should carefully consider when is the appropriate stage of the process to communicate expectations about price elements of the proposal.

Prior to entering into complex negotiations, government should identify and document a negotiation strategy which includes price considerations and the parameters of a value for money direct deal.

2.9 Complying with all probity requirements

Ensuring any direct dealing processes are consistent with the guiding principles above is a key part of the State meeting its probity obligations.

However, the guiding principles and these guidelines are not an exhaustive statement of the State’s probity obligations.

At all times agencies must consider and comply with all applicable probity requirements, including the ICAC guidelines and the NSW Procurement Policy Framework.

3. Core requirements for direct dealing

3.1 Overview

There are several core requirements outlined in this section that should be satisfied as part of every direct deal process.

The core requirements will help agencies to meet their fundamental probity obligations and to deliver outcomes that maximise value for the people of NSW.

While the core requirements should be satisfied for all direct deals, agencies retain discretion regarding how to implement the core requirements.

Deal-specific process and governance arrangements should be informed by the size, complexity, risks and level of cross-government impact in relation to the project.

Consequently, the level of governance and approvals may vary by project. For example, the appropriate framework for a bespoke, large and complex direct deal may differ from the appropriate framework for less complex small-scale direct dealing.

If agencies have any questions or require further guidance on implementation of the core requirements, they should contact Investment NSW.

The guidelines are not intended to absolve agencies of any existing legal requirements. They should be aware of their legal obligations under the Public Works and Procurement Act 1912 and the EPP Direction.

3.2 A documented justification for direct dealing

Before entering any discussions with a potential counterparty, the justification for considering direct dealing must be established and documented.

Consistent with the ICAC guidelines and the NSW Procurement Policy Framework regarding complex market engagement methods, this justification should include consideration of:

- how the direct deal with the potential counterparty may allow government to achieve an objective consistent with the ICAC guidelines

- how the direct deal complies with any applicable requirements under the Public Works and Procurement Act 1912 and enforceable procurement provisions made by the NSW Procurement Board under that Act

- why direct dealing is the most suitable approach

- whether any other procurement or market engagement approaches were considered and if so which ones

- why a competitive process does not need to, or cannot, be conducted, but value for money can still be achieved

- any risks arising from the procurement method (including complaints and legal action taken under the Public Works and Procurement Act 1912).

The detail to be included with the justification must be commensurate to the significance, size and risk of the project, as well as reflecting the early stage of the direct dealing process.

In order to direct deal, approval of the justification for direct dealing must be obtained from an appropriate agency senior executive, the relevant portfolio Minister or Cabinet.

Given the inherent risks of direct dealing, agencies should seek an appropriately high-level of approval, commensurate with the size and complexity of the transaction. Approval should be sought prior to entering any discussions or negotiations with the counterparty.

The justification for direct dealing must remain robust throughout the transaction and it may need to be retested at certain points throughout the project. In the event of a shift in policy, or a change to the structure or scope of the transaction, it is important for the project team to test whether these changes impact the justification, and whether direct dealing remains appropriate.

A direct deal between the NSW Government and a private sector entity was commenced after a failed market process indicated that there were no other operators interested in the project. This provided a justification for the NSW Government to deal directly with the counterparty.

However, during negotiations the counterparty sought to materially alter the scope of the transaction, as they did not believe that the project was financially feasible if certain requirements were included.

The project team had to consider whether the justification for direct dealing was still legitimate, given that the original tender process had expressly included the requirements that the incumbent provider sought to remove.

It is a requirement under the EPP Direction that an agency must not substantially modify the requirements of the procurement when conducting a limited tender following failure of a competitive procurement process.

Contravention of this obligation may create grounds for suppliers that participated in the original procurement process to take action in the Supreme Court seeking payment of compensation for the costs they incurred in preparing bids.

In this case, the project team determined that the proponent was attempting to substantially modify the requirements of the procurement and as such, the justification for direct dealing was no longer legitimate and the direct deal could not proceed.

3.3 A robust governance framework

A robust governance framework must be established prior to entering discussions with a potential counterparty.

For bespoke direct deals of significant size, risk and cross-government impact, this will generally require setting up transaction-specific governance processes and bodies, including:

- establishing an independent body to oversee the direct dealing (steering committee)

- a team to engage in discussions and negotiations with the counterparty (discussion/negotiation team)

- a panel to evaluate the direct deal (evaluation panel).

It will also generally require preparing appropriate documentation to govern the direct dealing process, which should cover:

- the processes for how agencies and the counterparty interact

- how government will evaluate the potential direct deal to determine whether it should be accepted

- how risks will be identified, mitigated and managed at each phase of the process

- what government’s negotiation strategy will be to ensure a value for money outcome.

For more routine, small-scale direct dealing, relevant governance mechanisms or agency procurement processes may already be established.

For example, an agency may have existing procurement policy documents that govern direct dealing, or existing standing bodies delegated with the power to consider or oversee potential direct deals.

Reference to steering committees throughout this document generally includes these existing oversight bodies where relevant.

Regardless of the nature of the direct deal, and the appropriate level of governance, the governance framework and related key documentation must be approved at an appropriate level of seniority.

In the case of bespoke direct deals, this will generally be the steering committee, which should also consider the justification for direct dealing to confirm it is valid and appropriate.

While the appropriate level of governance may vary, best practice guidance on governance for more significant direct deals is set out in section 6.

Agencies have their own procurement policies which set thresholds below which the agency is permitted to directly source services. These types of small-scale transactions are not captured by these guidelines.

3.4 A comprehensive evaluation of the proposal

Before government considers accepting any binding documentation regarding the direct deal, a comprehensive evaluation of the direct deal should be undertaken.

Agencies must evaluate a clear commercial proposition (proposal) from the counterparty.

Depending on the appropriate staging and governance for the particular transaction, the proposal for submission to government for evaluation may include proposed binding terms for both the State and the counterparty (binding offer) as well as proposed contract documentation to implement the direct deal (transaction documents).

For larger transactions, the proposal should then be evaluated by an independent evaluation panel to determine whether the proposal satisfactorily meets pre-determined evaluation criteria.

While the evaluation criteria may vary depending on the nature of the transaction, at a minimum it is critical that the following is assessed:

- whether the justification for direct dealing has been demonstrated

- that the counterparty has the capability and capacity to deliver the proposal.

- whether the proposal represents value for money for the State, including that the proposal is affordable and that any returns to the counterparty are appropriate given the nature of the direct deal and the risks or benefits that arise from it

- whether the proposal presents an acceptable risk allocation to the State.

Agencies must also clearly communicate the evaluation criteria to the counterparty at an early stage of the process to help focus negotiations and ensure the counterparty is aware of the criteria that will need to be satisfied for the direct deal to be accepted by government.

It is also critical that agencies establish how they will evaluate the proposal prior to its receipt. This can generally be achieved through the preparation of an evaluation plan, which should be approved at an appropriate level of government, or by a documented approach to evaluation in existing procurement process policies.

The standard of satisfaction and evidence required during an evaluation may vary at each stage of the direct deal process. For example, when considering whether to progress a proposal to direct negotiations, it is unlikely that detailed financial analysis will be finalised. It would therefore be difficult to definitively conclude whether the proposal represents value for money at that time.

In such circumstances, it is acceptable that the standard of evaluation is limited to whether the proposal is capable of representing value for money (that is, whether there is the potential that the proposal will result in a value for money outcome).

The standard of evaluation that will be applied must nevertheless be clearly set out prior to undertaking the evaluation, such as through documentation in the evaluation plan.

Section 5.1 outlines best practice guidance on evaluation criteria that could be applied.

The EPP Direction sets out criteria where it is not considered appropriate to deal with a counterparty.

This while relevant for direct deals relating to procurement this may be considered for direct deals beyond those covered by the EPP Direction.

3.5 Approvals for key decisions

At a minimum, agencies must seek appropriate approvals for key decisions in the direct dealing process, including:

- the justification for considering direct dealing

- the decision to enter into formal negotiations with the counterparty (direct negotiations). Approval to enter into direct negotiations may also coincide with the approval of the justification for considering direct dealing if it has already been clearly established the counterparty is willing to enter into direct negotiations

- whether to accept any binding offer, transaction documents or other binding documentation.

The outcomes of the decisions listed above should be appropriately documented. Further information on approvals is outlined in section 6.3.

Depending on the nature of the direct deal, the required approval level may be an appropriate agency senior executive, Minister(s), or Cabinet (including relevant Cabinet sub-committee).

Given the varied nature of direct deals, these guidelines do not mandate a required level of approval. Nevertheless, when determining approval levels agencies should consider:

- the circumstances of the project or transaction, including the significance to Government objectives, financial value, risks and cross-government implications

- agencies own delegation limits and processes for approval

- for direct deals relating to procurement, the agency’s level of procurement accreditation and any requirements to seek concurrence or assurance of the procurement process from another agency

- the Cabinet guidelines regarding when agencies must seek approval from Cabinet on matters that affect the government as a whole.

Where Cabinet approval is required, agencies should also consider the Cabinet guidelines to determine the appropriate Cabinet committee.

Where agencies are uncertain regarding the appropriate approval process, they should seek guidance from Investment NSW.

Agencies must also consider whether entering into direct deal documentation with the counterparty requires the approval of the Treasurer under the Government Sector Finance Act 2018 (NSW).

This may be necessary where entering into documentation constitutes a ‘joint venture’ as defined in the Act, which can, in certain circumstances, also include where non-binding documentation such as a memorandum of understanding or term sheets are entered into. Agencies should consult with NSW Treasury to determine whether this is the case.

Approval by government of the above decisions does not constitute approval under other independent or statutory processes. Counterparties will be responsible for obtaining all other such approvals, including, for example, statutory planning, environment and heritage approvals.

A NSW health agency regularly undertakes small scale procurements for a variety of services, which often require specific expertise and experience.

Where there is only one supplier with the capacity to undertake the proposed scope of works, the health agency may deal directly with the supplier by seeking an exemption from the requirement to conduct an open tender.

To deal directly with the supplier, an agency senior executive must approve the application for the exemption.

The approval of the chief procurement officer is required for all direct negotiation exemptions and must be based on the assumption that this procurement method will deliver value for money.

4. Best practice guidance: direct dealing process

4.1 Best practice direct dealing process

The process outlined below provides best practice guidance on an example structured process that agencies can implement when direct dealing. This process aligns with the guiding principles in section 2 and ensures the core requirements identified in section 3 are met.

It is recommended that agencies use the approach outlined in the best practice guidance as a starting point and only deviate where there is robust justification for doing so, having regard to the size, complexity and risks associated with each direct deal.

For less complex direct deals, it may be appropriate to refine the number of stages, or the governance structure, to most effectively manage the assessment of any proposal and ensure the process is fit for purpose. This may include where the project scope is less complex, the transaction value is relatively low or there are only a small number of issues that require negotiation.

For example, some agencies conduct routine, small scale procurement via direct dealing which may warrant a simplified governance structure or may be appropriately undertaken under existing agency procurement processes provided those processes satisfy the core requirements and are consistent with the guiding principles.

Regardless of the processes ultimately adopted, the milestones or stages should be discussed and clearly established with the counterparty to prevent unnecessary expenditure, align expectations and to provide confidence for the counterparty to continue.

There may also be merit in building in checkpoints for evaluating the performance of each party to ensure lessons learned are captured and can be implemented for the next stage.

Agencies should contact Investment NSW if they require guidance on appropriate process staging and how to adapt the best practice guidance to a specific project context.

Where government assesses a proposal as not meeting the evaluation criteria, government should reserve its right to go to market, subject to intellectual property constraints for unique proposals or solutions. The counterparty should be provided with the opportunity to participate in any procurement process should the concept be offered to the market.

General guidance on the stages of the best practice direct dealing process is outlined below.

Procurements covered by the EPP Direction

When a direct deal relates to a procurement covered by the EPP Direction, the agency is required to document the reasons for using limited tendering to conduct the procurement.

It is strongly recommended that the agency seek legal confirmation that the rationale satisfies the requirements of the EPP Direction.

Government regularly engages with non-government counterparties in the course of its day to day operations. Sometimes these conversations may lead to the identification of a potential opportunity to work with a non-government counterparty to achieve government’s objectives.

In this early stage, it may not be clear whether a potential counterparty may be interested in a direct deal or whether direct negotiations with the counterparty can be justified.

If this is the case, it may be useful to hold preliminary discussions with the counterparty to determine whether interest exists and ascertain the high-level feasibility of the potential direct deal, prior to committing government resources and establishing a formal governance framework.

Preliminary discussions should be exploratory in nature and confined to establishing the potential for direct dealing. Preliminary discussions do not commit either the counterparty or government to entering into formal discussions.

Before entering into formal discussions with a potential counterparty, the justification for considering the direct deal must be documented. As per section 3.2, this should include outlining:

- how the direct deal with the potential counterparty may allow government to achieve an objective consistent with the ICAC guidelines

- why a direct deal is an appropriate procurement approach, in particular in comparison to a competitive market procurement process

- whether any other procurement approaches were considered and if so which ones

- how the direct deal has been structured to be consistent with the ICAC Direct Negotiation Guidelines and, if applicable, agency procurement policies, the NSW Government Procurement Policy Framework, and legal obligations under the Public Works and Procurement Act 1912

- why direct dealing is the most suitable procurement approach

- any risks arising from the procurement method.

The detail to be included with the justification should be commensurate to the significance, size and risk of the project, as well as reflecting that the direct deal is at an early stage of the process.

Agencies must obtain approval from the appropriate approval authority (such as an agency senior executive or the relevant portfolio Minister) of the justification for considering direct dealing.

Formal discussions with a counterparty may be undertaken to:

- outline government’s strategic objectives and requirements, to enable the counterparty to formally submit a proposal to Government

- for government to be in a position to effectively evaluate the proposal from the counterparty, to determine whether it is appropriate to enter into direct negotiations.

A robust governance framework must be established prior to entering into formal discussions. The governance framework and related key documentation, including the risk assessment and management plan, must be approved by the relevant governance body, such as the steering committee.

Formal discussions may address a range of technical and commercial issues, and more broadly cover anything necessary to enable the submission and evaluation of the counterparty’s proposal.

Submission of the proposal may also include proposed high-level project scope, commercial principles and preliminary feasibility analysis.

Depending on the level of project development it may also be appropriate for the counterparty to propose a non-binding term sheet at this stage.

Formal discussions do not themselves constitute direct negotiations unless approval has previously been obtained at that stage to enter into direct negotiations.

If that is the case, no commercial terms should be agreed prior to evaluation of the proposal and receipt of the requisite approval. The focus of formal discussions should enable the counterparty to understand government’s objectives so a proposal can be submitted and evaluated.

At all times in formal discussions, agencies should preserve government’s capacity to achieve value for money by ensuring binding commitments are not made until value for money can be assessed.

Milestone: Evaluation of formal proposal

Generally, the counterparty will submit a formal proposal to government at the conclusion of the formal discussions.

The evaluation panel should be constituted prior to receiving the formal proposal, and the evaluation plan, including evaluation criteria, finalised and approved by the steering committee.

The evaluation panel and steering committee should also consider if the evaluation criteria will be disclosed to the counterparty during the formal discussions.

Once the counterparty’s proposal has been submitted it should be evaluated by the evaluation panel and the panel’s recommendation put to the steering committee for approval.

If the recommendation is for the proposal to proceed for further detailed consideration, appropriate approvals should be sought for the submission to proceed.

Depending on the project characteristics this may be an appropriate agency senior executive, Minister(s) or Cabinet (including relevant Cabinet subcommittee).

Where Cabinet approval is required, agencies should consider the Cabinet guidelines to determine the appropriate Cabinet committee.

The purpose of direct negotiations is for government and counterparty to negotiate the terms of the direct deal to enable the counterparty to submit a binding offer to government that may be capable of acceptance.

The binding offer may include documents that the counterparty proposes government enters into to give effect to the binding offer, if accepted (transaction documents).

Negotiation meetings provide a forum for direct interaction between NSW Government and the counterparty during direct negotiations. The sessions should allow for effective and efficient resolution of any outstanding items or issues identified with the proponent’s proposal.

Where agencies are undertaking complex negotiations to resolve outstanding issues, it is best practice for agencies to develop a negotiation plan. Further information on what this document should contain is outlined in section 6.6.

To enable the evaluation panel to effectively assess any binding offer, the negotiation team may arrange for relevant due diligence to be undertaken concurrently with direct negotiations.

The counterparty may be required to provide all relevant necessary information to enable the due diligence, on an open book basis, including information about:

- any contractual rights key to the proposal, such as land ownership, options or intellectual property

- the financial feasibility of the proposal, including detailed financial modelling displaying all cash flow line items, financing assumptions, and the counterparty’s internal rate of return

- valuations of any land or other commercial values that form part of the proposal

- planning pathways and approvals

- construction methodologies

- other approvals, such as relating to environment, heritage or rail.

Milestone: binding offer

The evaluation plan developed in stage 1b may address the evaluation criteria and process to evaluate the binding offer.

If this has not occurred, the evaluation criteria must be finalised prior to receipt of the binding offer, along with any relevant approvals by the steering committee or others.

The evaluation panel, or relevant body, should assess any binding offer against the evaluation criteria. The evaluation should include a recommendation as to whether the binding offer and proposed transaction documents satisfy the criteria and should be accepted by government.

A value for money assessment may include comprehensive consideration of both the direct and indirect financial costs and benefits to government, as well as a comprehensive assessment of the potential economic and strategic benefits of the proposal.

This valuation may also involve undertaking benchmarking analysis, sensitivity testing, or where appropriate, the use of comparative financial models like public sector comparators or shadow bid models, based on a reference project.

The evaluation panel’s recommendation must then be provided to the steering committee for endorsement. If endorsed, approval should be sought regarding whether to accept the binding offer.

Depending on the project characteristics, this may be an appropriate agency senior executive, Minister(s) or Cabinet. If Cabinet approval is required, consider the Cabinet Guidelines to determine the appropriate Cabinet Committee.

A further round of direct negotiations may be appropriate where the binding offer requires further negotiation or documentation, or there are outstanding issues requiring resolution.

In circumstances where the counterparty’s stage 2 proposal has a high-level of acceptability, this stage may be unnecessary or relatively short. In other cases where there are significant issues identified with the stage 2 proposal, this stage may be more protracted.

It may be necessary to undertake a further evaluation of the final binding offer depending on the extent to which the final binding offer departs from the binding offer. Following the further evaluation, approval of the final binding offer should be sought.

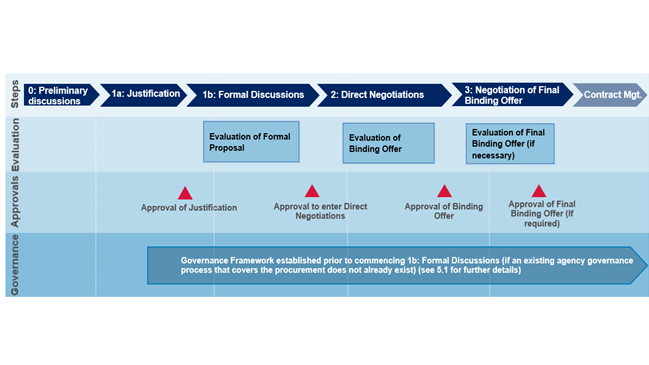

4.2 Structure diagram

The diagram below represents the best practice direct dealing process described in section 4.1.

This example represents a process that involves evaluation of a formal proposal as well as evaluation of a binding offer.

However, projects that are not particularly complex or low value may not require such a detailed process.

5. Best practice guidance: evaluation

5.1 Evaluation criteria

While the evaluation criteria to be used to evaluate proposals may vary depending on the nature of the direct deal, in all circumstances agencies should ensure the criteria cover off the core requirements in section 3.

Click on each criteria to view best practice guidance on one approach to evaluation criteria agencies can use to satisfy the core requirements:

Demonstration of the justification for why it is appropriate to direct deal. This is a threshold issue that determines whether direct negotiations can progress.

In evaluating the justification, agencies should fully examine claims that direct negotiations are the most suitable course of action, as well as explore any alternative courses of action.

In the case of government-initiated direct deals, the nature of this criteria will vary depending on the circumstances of the potential direct deal.

For example, if the justification for direct dealing is that ‘a completed competitive process failed to produce a satisfactory offer and the agency does not expect a repeat of the process to produce a better result’, the criterion should evaluate the evidence that suggests a better result is unlikely.

If the justification is that the counterparty is in a unique position to deliver the outcomes the State is seeking, the agency should evaluate the evidence to support this and test whether there are any other alternative options.

To evaluate value for money, agencies should consider the following questions:

- Does the proposal deliver value for money to the NSW Government?

- What are the net economic benefits of the proposal (the status quo should be defined)?

- Is the proposal seeking to purchase a government asset at less than its value in exchange for other services?

- Does the proposal provide time or financial benefits/savings that would not otherwise be achieved?

A proposal is value for money if it achieves the required project outcomes and objectives in an efficient, high-quality, innovative and cost-effective way with appropriate regard to the allocation, management and mitigation of risks.

While value for money will be tested appropriately in the context of each specific proposal, factors that will be given consideration are likely to include:

- quality of all aspects of the proposal, including: achievable timetable, clearly stated proposal objectives and outcomes, design, community impacts, detailed proposal documentation and appropriate commercial and/or contractual agreements (including any key performance targets) and a clearly set-out process for obtaining any planning or other required approvals

- innovation in service delivery, infrastructure design, construction methodologies and maintenance

- competitively tendering aspects of the proposal where feasible or likely to yield value for money

- cost-efficient delivery of government policy targets

- optimal risk allocation (refer to criterion below).

Evaluation of value for money may also include, but not be limited to the following quantitative analysis:

- interrogation of the proponent’s financial models to determine the reasonableness of any capital, land acquisition, service and maintenance cost estimates and, if relevant, revenue estimates (including the appropriateness of any user fees or prices and estimates of quantity levels)

- the use of independent experts or valuers, benchmarking analysis, sensitivity testing, and where appropriate, the use of comparative financial models like public sector comparators or shadow bid models, based on a reference project.

Does the proposal meet a project or service need?

What is the overall strategic merit of the proposal? Agencies should identify the NSW Government objectives that are sought and identify how direct dealing will achieve this objective.

What is the opportunity cost for government if it were to proceed with the proposal?

Is the proposal consistent with government’s plans and priorities? Does the proposal deliver on any specific State outcome or Premier’s Priority?

Does the proposal have the potential to achieve planning approval, taking into account relevant planning and environmental controls?

Does the proposal contribute to meeting the objectives of district plans, regional plans and metropolitan plans and delivering on housing targets?

Consideration will be given to whether the proposal would require government to re-prioritise and re-allocate funding.

Is the proposed return on investment to the counterparty proportionate to the proponent’s risk exposure and industry standards?

Is the proposed return on investment justified by the proponent’s internal modelling and assumptions (noting consideration of this criteria will require a counterparty to disclose key financial information and assumptions on an open book basis)?

Where feasible, the proposed rate of return may be subject to independent review or benchmarking.

Does the counterparty have the experience, capability and capacity to carry out the proposal?

What reliance does the counterparty have on third parties?

Does the proposal require government funding or for government to purchase proposed services? Does government have these funds available or budgeted and if not, what source would be proposed?

Where State funding is required, government may undertake or require the counterparty to undertake a (preliminary) business case or an economic appraisal at stage 2 (where appropriate), consistent with the NSW Government Guide to Cost-Benefit Analysis (TPP17-03).

Regardless of the outcome of the business case/economic appraisal, the proposal still needs to be affordable in the context of government’s other priorities and to be considered as part of the NSW budget process.

What risks are to be borne by the counterparty and by government? Appropriate risk allocation and quantification may also be considered under the value for money criterion.

Does the proposal require environmental and planning approvals? If so, has the process been appropriately considered, including whether government or proponent bears the risks associated in obtaining the approvals.

6. Best practice guidance: governance

6.1 Governance arrangements

Governance arrangements should generally include:

- management and co-ordination through the relevant lead agency

- a single, overarching steering committee

- an evaluation panel

- a clear approach to evaluation, negotiation and contracting.

Depending on the size and complexity of the transaction, governance arrangements may also include whole-of-government management and coordination through representation on the relevant steering committee.

Government should establish appropriate governance arrangements once the justification for direct dealing has been confirmed (if not already in existence). The arrangement will detail:

- the make-up and responsibilities of the steering committee and assessment/technical panels

- management of confidentiality and conflict of interest

- provide details of the appointed proposal manager and probity advisor.

For more information on how to manage conflicts of interest, please refer to the ICAC's 2019 guide, Managing conflicts of interest in the public sector.

In addition, proposals will be assessed under Infrastructure NSW’s Infrastructure Investor Assurance Framework, where appropriate.

The roles and responsibilities outlined in section 6.2 present best practice guidance for direct dealing and should be applied and refined depending on the size, complexity and risk associated with the project. The core requirements for governance arrangements for a direct deal are outlined separately.

6.2 Roles and responsibility

Click on each role to view the responsibilities that may generally be included in the direct dealing process.

The counterparty is generally required to:

- meet with the agency team to establish and document the justification for considering direct dealing

- prepare and submit a proposal to government for assessment, providing government with all information necessary to enable assessment of the proposal on an open book basis

- provide a binding offer at the conclusion of stage 2 and a final binding offer where necessary

- comply with all applicable process and probity requirements and engage in discussions and direct negotiations with government in a good faith attempt at reaching agreement on a direct deal capable of acceptance

Given the risks, some direct deals will require Cabinet approval for progression between stages.

However, the number and frequency of approvals may vary depending on project specifics.

The required approval process will be described to the counterparty.

As the owner of this policy, Investment NSW provides advice within government on direct dealing arrangements.

In addition, Investment NSW is available to chair steering committees where a whole-of-government governance structure is warranted or where it is deemed the lead agency for a proposal.

The role of the steering committee is to provide strategic oversight and guidance in respect of all aspects of the direct dealing process. While the exact scope of responsibilities may vary, these may include:

- overseeing all discussions and negotiations between NSW Government and the counterparty

- providing strategic input, advice and direction to NSW Government representatives holding discussions or negotiations with the counterparty

- coordinating with and, to the extent necessary, ensuring alignment with other existing government projects or policies that interface with or may be impacted by the direct deal

- monitoring the discussion/negotiation process to ensure appropriate probity and accountability measures are maintained

- ensuring relevant policy and project assurance processes are adhered to

- approving key governance documentation, including the steering committee terms of reference, the governance plan, the discussion/ negotiation plan, the evaluation plan and any separate probity plan

- confirming the approach to assessing value for money

- considering recommendations from the evaluation panel and make recommendations to Cabinet and its committees, where appropriate, at key decision points on whether to proceed with the direct deal.

The steering committee should generally include representation from key agencies with strategic interests in the outcome of the direct deal.

Representation from Investment NSW and NSW Treasury on a steering committee is an effective way to ensure a diversity of views about the transaction is represented within the governance structure.

In the case of smaller or less complex transactions, a diversity of views may be achieved through representation from different parts within the same agency, removing the requirement for a representative from Investment NSW or NSW Treasury.

The seniority of steering committee members should be commensurate to the strategic significance, value and risk of any potential direct deal.

The role of the negotiation team is to hold discussions with the counterparty during the relevant process stages and the negotiation meetings, if the proposal progresses to negotiations of a final binding offer.

The role of the discussion/negotiation team may include:

- holding negotiation meetings with the counterparty to discuss the proposal, provide feedback and clarify NSW Government’s requirements in relation to the potential direct deal, and to seek resolution to identified issues

- working cooperatively with the counterparty with a view to developing a binding offer capable of acceptance by government

- overseeing a multi-disciplinary team to undertake all work required to provide the necessary guidance and input to enable the counterparty to put forward its best binding offer to government

- facilitating the preparation and provision of information between the Government and the counterparty

- providing regular progress updates to the steering committee and seeking guidance where required.

The lead agency may nominate a proposal manager to be the counterparty’s key point of contact in government regarding the direct deal.

Once the justification to direct deal is confirmed, the proposal is subject to an assessment process. Counterparties must not contact government ministers, advisors or officials regarding the submitted proposal outside of the formal assessment process. This includes organisations authorised to act on the counterparty’s behalf.

The role of the proposal manager may include:

- receiving any proposals

- facilitating the assessment panel or steering committee/proposal-specific steering committee as appropriate

- acting as contact point for the counterparty

- facilitating interactions between the counterparty and government

- facilitating the preparation of information provided to the counterparty

- coordinating preparation of assessment reports

- providing assistance to government agencies with a responsibility for assessing any proposal.

The proposal manager may also be a member of the discussion/negotiation team.

The evaluation panel’s role is generally:

- evaluating any proposal from the counterparty, including to enter into negotiation of final binding offer

- making recommendations to the steering committee as to whether the proposal should progress, including progression to negotiations or whether the binding offer should be accepted and any proposed transaction documents entered into

- preparing evaluation reports as required by the steering committee.

The evaluation panel should be established prior to the receipt of a proposal from the counterparty.

Membership of the evaluation panel should be approved by the steering committee, typically as part of the evaluation plan.

To ensure the independence of the evaluation panel, best practice is that the membership of the panel does not include members of the discussion/negotiation team.

It may nevertheless be appropriate to have some members in common where the proposal is particularly complex and it is necessary to properly evaluate the proposal for the panel to have access to detailed knowledge of the discussions/negotiations held with the counterparty. If this is the case, this should be documented as part of the evaluation plan approved by the steering committee.

Where a proposal is particularly complex, a preferable alternative to having members common to both the discussion/negotiation team and evaluation panel is for the discussion/negotiation team to hold joint briefings for the evaluation panel and steering committee to keep them informed on progress.

A probity advisor should be appointed for large-scale projects or where the steering committee considers probity risk sufficient to warrant the appointment.

The role of the probity advisor is to monitor and report on the application of the probity fundamentals during the assessment process. The probity advisor may:

- assist in the development of a governance plan where applicable

- provide a probity report at the end of each evaluation stage to be considered by the steering committee as appropriate before the decision to proceed to the next stage or otherwise

- provide interim reports at key milestones of the assessment or at the behest of the steering committee as appropriate

- report to the chair of the steering committee as appropriate and will be available to counterparties to discuss probity related matters

- escalate probity concerns to the secretary of the lead agency or a pre-identified escalation contact point.

In the absence of a probity advisor, this role may be undertaken by the proposal manager or the process may be subject to a probity audit.

Counterparties are able to request the appointment of a probity advisor. Whether or not a probity advisor is appointed, the project team, including the proposal manager, discussion/negotiation team and evaluation panel, retain accountability for ensuring impartial and probity-rich management practices throughout the direct dealing process.

Advisors may provide expert advice to the discussion/negotiation team, evaluation panel and steering committee as appropriate. Examples of key advisors that may be appointed to provide specialist expertise to assist in project development, negotiation and assessment:

- legal

- commercial or financial

- technical

- probity.

Other advisors may be appointed where specialist input is required.

A specialist project director may be appointed at the formal negotiations stage, particularly for large and/or complex projects.

Advisors are to follow all project governance and probity requirements.

6.3 Approvals

Appropriate approvals are a key part of governance arrangements and should be sought at key stages of the direct dealing process.

Additional approvals may be required depending on the stages in a direct dealing process and the size, complexity and risk of the proposal.

6.4 Disclosure

In the interest of good governance and to maintain transparency and accountability, there may be circumstances in which it is appropriate to publicly disclose information relating to direct deals. This is particularly likely to be necessary in the case of large scale and complex transactions or transactions with a high level of public scrutiny.

At times, Investment NSW undertakes high profile, complex, large-scale direct deals in collaboration with other agencies that relate to important public spaces or interface with key government infrastructure.

Due to the nature and profile of the direct deals undertaken by Investment NSW, publication of assessment outcomes may be appropriate and in the public interest. In these cases, Investment NSW or the partner agency will publish summary assessment outcomes in the appropriate location.

Direct dealing is only undertaken in circumstances where a competitive tender is not possible or advisable. As direct dealing is an exception to the norm, publication of summary assessment outcomes may be necessary to maintain transparency and accountability.

Agencies should consider the size and complexity of the deal when considering whether publication of summary assessment outcomes is required.

Agencies must comply with existing requirements (such as requirements to publish relevant contract details under GIPA or requirements set out in existing procurement policy documentation).

Where contracts are required to be published under GIPA, Investment NSW recommends the agency consider making the assessment outcomes publicly available.

6.5 Monitoring

Investment NSW may establish a structured periodic review to assess the effectiveness of the approach to direct dealing.

6.6 Documentation

Click on each key document below to view best practice guidance that may be required for a direct dealing process.

Agencies should consider the project specifics and staging of the process in order to identify whether a document is required. All governance documentation should generally be approved by the steering committee.

The governance plan should set out the governance arrangements, roles and responsibilities. It may also set out appropriate probity protocols.

If not set out in the governance plan or if a direct deal has significant probity risks, it may be appropriate to prepare a separate probity plan setting out the probity protocols that must be followed by government and the counterparty.

The probity plan should include the formal protocols for managing conflict of interest declarations that meet probity requirements and withstands scrutiny.

Regardless of the stages involved in a direct deal process, documentation that sets out the protocols and processes for how government and the counterparty interact is required to ensure any discussions and/or negotiations are undertaken in a fair and transparent manner.

These may take the form of a cooperation or participation agreement or, in the context of formal negotiations, they may sometimes be executed as a deed and described as a deed of direct negotiation.

This documentation may include, for example:

- provisions regarding how the Government and counterparty communicate

- how discussion/negotiation meetings are held

- requirements around the provision of information and confidentiality

- prohibitions on lobbying during the direct deal process.

The process documentation should be signed by government and the counterparty prior to the commencement of formal discussions or direct negotiations, to ensure appropriate processes are in place to govern those stages of the direct deal process.

Agencies should also generally prepare internal documentation about government’s approach to any discussions or negotiations with the counterparty (generally known as a discussion/negotiation plan).

Some considerations that may be covered in the discussion/negotiation plan include:

- governance arrangements, if not already set out elsewhere

- roles and responsibilities of different agencies and discussion/negotiation team members

- government’s approach to discussion/negotiation meetings, including protocols around timing, minutes, and presentation of the State’s position

- negotiation parameters and a negotiation strategy, including documenting a minimum acceptable price where the direct deal relates to the sale of a government asset

- a statement of government requirements to be met by the direct deal.

Employees and advisors of the counterparty may be asked to sign confidentiality deeds where they are provided with confidential government information.

If the information is particularly sensitive, employees and consultants may be required to personally sign deeds.

In other circumstances, it may be appropriate that deeds only be signed at company level, with individual employees or consultants to sign an acknowledgement of their confidentiality obligations under the deeds.

Government employees involved in the project should also sign documentation acknowledging their confidentiality obligations and declaring any conflicts of interest they may have. This should generally include members of the discussion negotiation team, evaluation panel and steering committee.

All confidentially deeds or acknowledgments, and declarations of conflicts of interest, should be tracked in a register. The proposal manager should generally be responsible for overseeing the register unless otherwise provided in the governance plan.

The confidentiality documentation should be signed prior to the commencement of initial discussions. The proposal manager should confirm if there are any changes to conflicts of interest declarations at the start of each steering committee and evaluation panel meeting.

The evaluation plan sets out the approach to evaluation of any submission from the counterparty.

The evaluation plan may cover the following:

- roles and responsibilities in relation to the evaluation

- evaluation panel members

- resourcing to enable the evaluation

- Government’s objectives for the direct deal

- evaluation criteria

- evaluation approach, including how scoring and evaluation panel meetings will be run

- any requirements or approaches to how particular evaluation criteria will be assessed

- whether any site visits, inspections, testing or certifications are required

- how value for money will be assessed.

The evaluation plan should be approved prior to commencement of the evaluation and receipt of the proposal from the counterparty.